The Deuce, the BUFF, the Constitution, the Bayonet

Longevity in warfare, and the functional waste the past hurls like a javelin at the future

Edited by Althea May Atherton

In June 1946, the US Army Air Forces issued the first contract for what would go on to become the B-52 Stratofortress. The venerable bomber, which was cutting-edge when it had a starring role in 1964’s Dr. Strangelove, is on track to reach an entire century in service. It is, in some sense, a Warship of Theseus, with parts replaced and crews generations descended from the first to pilot the planes.

What brought this longevity to mind recently was a contract for replacement engines that could serve it until the 2050s. I first saw this news in a June story from Defense One (it’s also where I first learned it was an Army contract that set it all in motion). And it led, as news like this so often does for me, to some Twitter speculation about the longevity of weapons.

Almost immediately, I realized my framing of “the longest serving piece of military technology” was too broad, but the answers provided were fascinating regardless of my poor choice of parameters. The majority of this is going to be a deep dive into weapon longevity, but before I get there, I wanted to talk a bit about why I’m so interested in weapon longevity.

In February 2008, a cannonball built for the Civil War exploded, killing a man in Virginia. It’s a death I think about a lot, the kind of item that filled a couple inches of alt-weeklies “news of the weird” columns, usually with a punchline about how the guy’s hobby was salvaging and restoring cannonballs. What did he expect, exactly, when he finally came across a live one?

Yet there’s something else, far more ominous than the grim joke, of a cannonball built in one century, persisting through a second, and killing someone in a third. Categories of weapons can endure for centuries. It’s rare that specific manufacturer models of weapons endure for more than a few decades, though there’s some notable exceptions. And this means that commissioning a weapon for an immediate war might mean authoring the death of someone else hundreds of years removed.

With no pretension that it is the comprehensive or conclusive list, here are some long-serving vehicles, weapon models, weapon types, logistical aids, and tactics.

Possible Longest Serving Vehicles, named

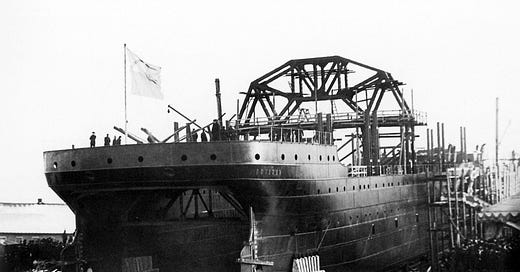

The USS Constitution, launched in 1797, is the oldest commissioned ship serving the US Navy. It is, I think, safe to say it was a warship from 1797 to 1828, with later stints as a training vessel, a floating barracks for new sailor recruits, and her present form, as an operational museum piece. It’s a remarkable history, though unless we count its use as a temporary jail during WWII, it’s hard to say it really had a centuries-spanning active military career.

Commissioned as the Volkhov in 1915 for the Tsarist military, the Kommuna submarine tender was active at least through 2015, having served as a salvage and repair ship under the Tsar, the Soviet Union, and the Russian Federation in that century.

Another contender of sorts is Sliabh na mBan, which car magazine Hagerty describes as “the oldest wheeled active-service military vehicle in the world” and “the internal-combustion equivalent to the USS Constitution.” It’s an armored car preserved as a sort of living museum, dating from 1920 and kept on active military rolls as a way to ensure the military funds its preservation.1

Longest Serving Weapon Class, named

Designed in 1918, introduced into service in 1933, the M2 Browning machine gun is almost certainly going to be the longest serving named model weapon by the time someone in 2121 revisits this listicle. Used as everything from a squad-carried weapon to one mounted on vehicles and ships, the M2 is an astoundingly durable and versatile design. (The M1911 pistol, also designed by Browning, currently has a few decades on “Ma Deuce,” but it’s been replaced as a standard service pistol.) Mass production is especially key for weapons like this, allowing both spare parts and familiar ammunition to circulate for decades.2

A possible contender for longevity is the Lee Enfield rifle, with the version first produced in 1904 seeing over a century of use. This passage by “The Gun” author C.J. Chivers, published in Foreign Affairs in 2011, has stuck with me for a decade:

“One of the Lee-Enfields captured by the marines in Marja bore a date stamp from 1915. This was a rifle that was manufactured as Kitchener's Army was massing for service on the western front, using ammunition made for service against the Third Reich, and now firing on U.S. troops in Afghanistan. “

I should note, quickly, that the eponymous gun of Chivers book is the AK-47 and its variants (like the AK-74). While they’re not yet close to the century mark, they will invariably get there.

To the point of ammunition: the Lee Enfield uses a .303 British caliber bullet, which has been in service since 1891. It’s contemporaneous with the 7.62×54mmR, introduced that same year and in use with a number of modern Russian-made weapons (though, notably, not the AK family).

Bullets aside, the current contender for longest serving firearm model, as best people in my mentions could find, is the British Land Pattern Musket, nicknamed the Brown Bess. It entered service in 1722 and was only taken out of service 129 years later, in 1851.

And while not specifically a class of weapon, the Dardanelles Gun built in 1464 gets its name from use against the British navy in 1807, or 340 years later.

Longest Serving Vehicle Type, no model name

There’s a couple possible contenders here, depending on how much we are allowing similar but not exact models to count as the same type of thing. Sixteenth century Galleys, seen as a continuation of 7th century BCE oar-powered warships like biremes, have an almost untouchable 2200-year history (to say nothing of the centuries that galley design was useful in a somewhat secondary capacity.)

As a product specifically built for gunpowder warfare over great distances, Ships of the Line date from the 1400s to the 1800s, with greater standardization in the vessel's design arriving by the 1700s. Like galleys on the calmer and shallower seas of the mediterranean, ships of the line had to be uniform enough to work in formation with others, while still allowing for variation based on what could reliably be produced.

Observation balloons, the longest serving category of military aircraft, date back to 1794, with modern sensor-laden models in use today. (Often tethered, though sometimes famously untethered).

Chariots as a category have a long-running and (as with much of antiquity) somewhat contested timeline of use. Roman historian Tacticus, a uh not entirely reliable narrator, records chariots used against Romans in battle in modern-day Scotland in 161 CE. The form, as at least a transport for war, dates back to at least 3000 BCE, with evidence of it in Mesopotamia, where it was an ox- or donkey pulled transport. Taken at its longest possible extent, or over 3000 years, is probably not quite the correct approach, given how much change there was in design, use, and refinement. It’s possible that the historians of the 4000s may look back and, instead of delineating between the Brown Bess and Ma Deuce, simply say that “firearms were a type of weapon used by humans from the 10th century onwards,” and I think it’s reasonable to take a similar approach to chariots as a super-broad category of military tool. We’ll revisit this in a moment, I promise!

Longest Serving Weapon Type, no model name

Treating all firearms as a single category brings us to the “Fire Lance,” essentially a small explosive add-on to a spear or halberd, which when lit produces an explosive blast. Removing the blade and refining the barrel turned fire lances into hand cannons, the earliest guns-that-were-guns, though variations with blades persisted for centuries. That’s not exactly a specific type of weapon as it is a category, though it leads neatly into what is the longest serving category (if not model) of military weapon: the spear.

Spears are easily the oldest kind of human-made weapon in existence, setting aside the use of found objects like rocks or simple clubs. Stone-tipped spears date back at least to 500,000 years. Wooden spears, easier to make and less likely to naturally preserve, have been found dating back to 400,000 years ago, and invariably predate stone-tipped spears, even if the evidence is harder to find.3

Pikes, used as we understand them first in ancient Macedon and then again from the 1300s in Europe, were eventually supplanted by bayonets, in part as the power of firearms increased and also as heavily armored cavalry charges fell out of favor. While it’d be a misread to describe pikes as in continuous use for that entire time, the conditions that made pikes favorable are not necessarily fixed, seeing as they entered use first as an adaptation to shorter infantry spears, and later as a reaction to cavalry charges.

The deep antiquity of spears isn’t particularly surprising. What’s more remarkable is that, through bayonets, they remain a present-day weapon, even if their role has fallen from “primary tool of war” to “one of several weapons of last resort.” Bayonets started as “plug bayonets” in the 1600s, where a blade had a mount that could be used to plug a gunbarrel and turn the existing gun into the shaft of a spear. As the plug prevented the weapon from firing, this mainly served as a tool for after exhausting ammunition, or for when close quarters fighting rendered the gun no longer useful. (Bayonets also complete a neat little cycle from firelances, which turned a polearm into a hand cannon, by turning a hand cannon back into a polearm).

Longest Serving Military tools, no model name

I wanted to wrap this up with a catch-all about a few other long-serving tools. Pack animals came up a lot, and while I’m hesitant to reduce, say, horses or mules to purely military kit, it’s not wrong to include the ways military needs shaped their breeding, use, and population numbers.

Canned food, or originally jarred food, dates back to the Napoleonic era, as a way to send preserved food on campaign with soldiers. It’s an invention that remains in place with militaries today, with the modern Meal Ready to Eat paired against that other staple of human conflict, a “rock or something.”

Carts, wagons, and wheeled transports can be dated, alongside the chariot, to around 3000-3400 BCE. Like the possibility of early Sumerian chariots used more as transports to combat, the role was more logistics tools than specific war machine, but it’s an important adaptation of a domestic technology to support a violent end (if, even, that distinction makes sense when applied.)

A vehicle I wrote about for Popular Science this month, the Expeditionary Modular Autonomous Vehicle, is simultaneously a semi-autonomous tracked- and sensor-laden robot, and also just a wagon built by the technology of the day.

What Did I Miss?

AMA: maps! You missed maps, Kelsey!

Maps have been around for about 3,000 years and have been crucial in military operations and colonization throughout much of their history and of course, paved the way for modern GPS and other geolocating technology. Fun fact: Ptolemy invented “Geography”, the latitude and longitude system and conversion of a world he knew was spherical to a two-dimensional medium, to improve the accuracy of his horoscopes, so yes, astrology has made historically important contributions to science and military technology!

This is at best a brief survey on the longevity of a whole host of weapons, but one interesting to contemplate, I think. (I wouldn’t have written it if I didn’t think so). If you’d like to chime in with more thoughts, outside the capricious whims of whenever I do a twitter thread, paid subscribers can gain access to the Wars of Future Past channel in the Discontents Discord, or leave comments below.

The Long Tail of the Sharp End of the Spear

This is mostly an exercise in armchair history, but if it has any merit beyond that, it is in thinking about weapons as a tool created in one era with consequences for the future. Given simple weathering, there’s finite limits on how long some weapons can remain in use, and especially finite risk. The greatest harm that can come from uncovering an ancient wooden spear is the risk of not realizing what’s on hand and damaging it.

It is perhaps unsurprising that I find gunpowder weapons, especially those fitting calibers of present mass manufacture, as the more durable hazard, all bullets aimed at the future. The durability of explosives in particular, and of those with built-in trigger mechanisms, is the most direct way the immediate need of the past threatens the future. In France, the annual ritual of unearthing unexploded bombs in the process of farming has earned the nickname “the Iron Harvest,” and it’s already into its second century.

Which brings us back to the B-52. I don’t think anyone involved in the design, planning, requirements, or acquisition of the bomber anticipated it reaching an entire century in service. It was, like most weapons, built for a next war, whatever that might be, imagined as taking place in the decade or so after it entered service.

Like other still serving machines from the dawn of the nuclear age, it was probably imagined that the B-52 would also fight in the last war, or at least the last war as part of an unbroken chain of recorded history. Which is as fitting a last note for this piece. Perhaps the most famous long-term planning for weapon detritus is the millennial-long storage of nuclear waste.

With the sterile title “Expert judgment on markers to deter inadvertent human intrusion into the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant,” the 1993 report breathed into the world as tidy a summation for the still-toxic byproducts of nuclear war preparations. It is, in a sense, the Ozymandias of the nuclear enterprise. In place of vast and trunkless legs, we have instead,

“Sending this message was important to us. We considered ourselves to be a powerful culture.

This place is not a place of honor... no highly esteemed deed is commemorated here... nothing valued is here.

What is here was dangerous and repulsive to us. This message is a warning about danger.”

This is specifically true of nuclear waste. It is also true of all material of war, and the bloody forging of battlefields.

Thank you all for reading this. I genuinely enjoy writing these newsletters roughly every fortnight (Althea and I apologize for our delay in sending this issue out), and I will keep writing them in some form for as long as I can sustain myself doing so.

If you’re in the mood for more free newsletters, may I recommend checking out what we’re doing over at Discontents? A couple weeks ago I participated in our second ever podcast episode, where we talked with Patrick Wyman about his book The Verge.

If you’re looking for tank models in continuous service (often as hand-me-downs from other militaries), here’s a list put together by PhD Candidate Andres Gannon, and a little thread about how long-serving WWII tank models are.

Here is where I should probably mention that, like many people without military experience, I picked up a lot of my ambient knowledge of firearms from video games. For me, specifically, the game I most learned from was Fallout Tactics, the 2001 squad-based combat game set in the post-nuke world of the 2160s or so. A vast array of weapons made up until the 2000s exist in game to be scavenged and used, but the most useful are the kinds that match the most common ammunition types.

In the process of writing this (which, yes, was mostly a dive in and around wikipedia sources), I learned that chimpanzees have independently invented spears for hunting purposes, with sharpened tips. For now, the tips are sharpened enough to injure but not kill prey.