Tarkin, Revisited

Andor and the materiel of Empire

Edited by Althea May Atherton.

This newsletter will contain spoilers for A New Hope, Return of the Jedi, Rogue One, The Clone Wars, and the first season of Andor.

The last shot of the finale episode of season one of “Andor”, tucked away as a post-credits reveal, shows droids assembling a structure in minute detail. Three droids cluster around a connector on a shiny-slick surface, and a fourth moves another one of the connectors on its back. More droids place the pieces into an elaborate lattice, as the camera zooms out, the inevitably of the reveal satisfying all the same. The connectors are part of a surface, the surface is part of a massive space object, the object is the Death Star.

This post credits scene, all score and CGI, would feel out of place if the show had not put so much effort into execution. When the droids are welding and transporting the connectors, there’s a visceral sense of the weight and heft of the pieces. For three episodes, in arguably the tightest storytelling stretch of an exceptionally tight show, protagonist Cassian Andor is part of a prison work crew tasked with assembling these six-sided pieces, in 12 hour shifts, until death. Human laborers are assembling these pieces, Cassian correctly surmises, because they are cheaper than droids would be for the Empire, and easier to replace.

Andor is a show about material realities, set in a universe where the material setting is backdrop to mythical sagas of superhuman champions. The Death Star shot is earned, because it puts the direct material labor into context. The Empire devised an especially cruel and efficient prison, yes, but the dehumanizing conditions were secondary to the Empire’s ultimate project, which is bending the material of the universe into a self-perpetuating machine of power and order.

The Death Star was first put on film in 1977’s Star Wars (later subtitled Episode IV: A New Hope in the 1981 rerelease). A New Hope is a film that leans heavily on the simple power of evocative phrases; we know the score between the Rebels and the Empire by name alone. The Empire replaced the Old Republic, with the vestigial Senate abolished in the film’s runtime. Apart possibly from lightsabers, the Death Star is the single most iconic technology in a film overflowing with rich details. Unassembled at the end of Andor, the Death Star’s laser array even looks like a lightsaber awaiting completion, broadly in line with the Disney-era canon explanation that both the Death Star and lightsabers are powered by the same source, Kyber crystals.

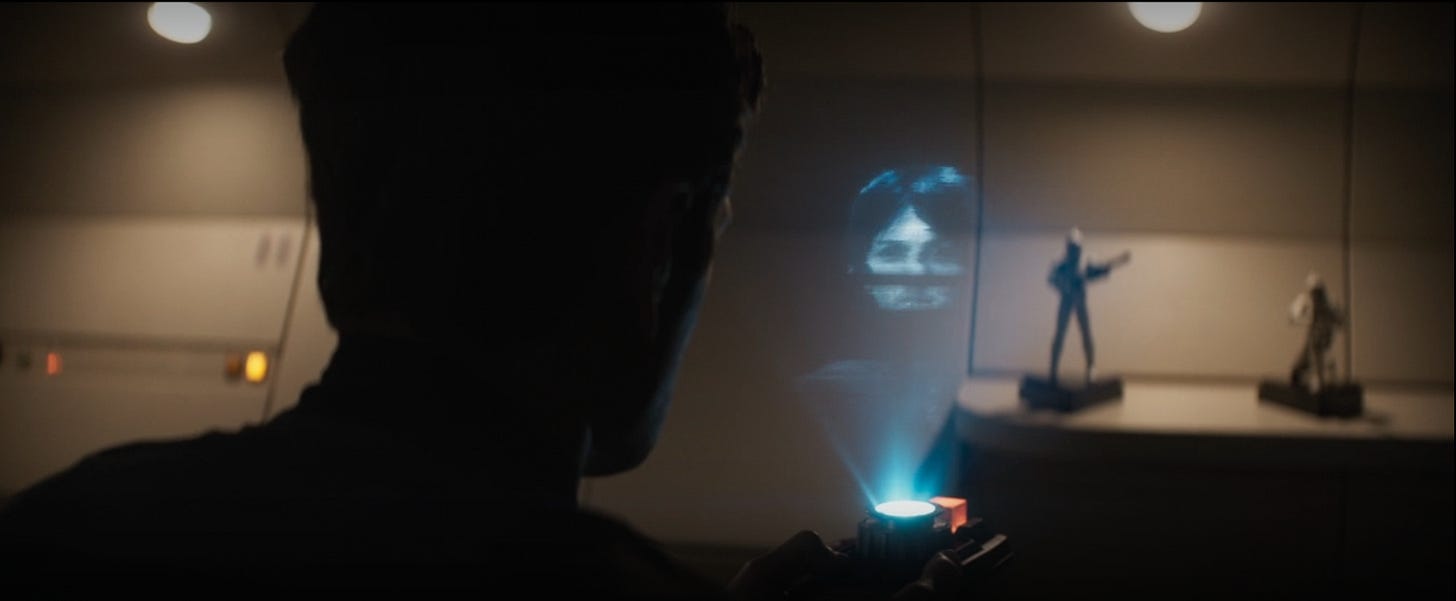

I’ve long been drawn to the material underpinnings of Star Wars, sometimes literally. I can clearly recall Star Wars micromachines filling my toy box, a seamless midway point between time spent playing with X-Men action figures in the sandbox and my teen years spent painting Warhammer armies. Cyril Karn, Andor’s dime-store Javert, has a moment in Episode 5 where he contemplates an image of his foe, while his childhood Clone Trooper action figures rest on a shelf in the background.

I’ve written before about how the weaponry of Star Wars, from fighter planes to close-up firefights, leans heavily on the cinematic constraints of World War II movies. The guided weapons and long range missiles that define modern warfare are absent, as is combat beyond line of sight, largely in keeping with what makes a shooting battle look compelling on-screen.

The Death Star is the exception to that. Drawing from World War II, the obvious reference point would be to atomic weapons, but the Death Star promises something on a far more horrific scale than even the obliteration of a city by a single bomb. The Death Star is, hauntingly, a weapon of counter-insurgency, one that is unmatched in the galaxy.

This is the heart of “The Tarkin Doctrine,” an explanation named for the Imperial Strategist most responsible for its creation. The Tarkin Doctrine first appeared in the Death Star Technical Companion, a 1991 role-playing game supplement. The Tarkin Doctrine is also the subject of my chapter in 2018’s “Strategy Strikes Back,” where a host of thinkers used modern strategy and Star Wars as mirrors to explain each other.

The Doctrine is, quickly, threefold: to prevent rebellions, the Empire must rule through military districts, rule by fear, and use the fear of a planet-destroying weapon to make every world quash its own rebellions before it becomes an Imperial problem.

Here’s how I concluded the piece:

How to create peace after decades of insurgency is a maddening question. Tarkin’s answer was elaborate, brutal, and focused on human cowardice. In a galaxy defined by war, Wilhuff Tarkin was one of the few even attempting to answer the right question.

It’s a punchy ending, though it’s fundamentally lacking, and not just because it treats planetary-scale murder as a strategic option worthy of consideration. What stands out, now, is how constrained the view is, the unspoken but clear assumptions that go into Imperial options. There are infinitely better ways to provide peace and stability than Tarkin considers, but by career, inclination, and institution, the better paths are all off-limits.

Weighing the options of indefinite and expensive armed garrisoning of the whole universe, or a weapon that can coerce a world into self-garrisoning against rebellion, Tarkin picked the latter with a Machiavellian touch and a bookkeeper’s satisfaction.

Early in my public writing days, in the summer of 2012, I launched Grand Blog Tarkin as a way for the DC National Security Set to talk about strategy in science fiction. The blog has lain dormant since 2017, its original URL squatted on after a missed payment. In a time where the actual military names projects after Star Wars trivia like the Kessel Run, Tarkin serves as a quasi-avatar of thinking about war from the institution of war.

Tarkin is absent from Andor, though he appears briefly in 2016’s Rogue One. Tarkinesque thinking is present throughout. In a series rich with compelling interwoven plots, Major Partagaz of the Imperial Security Bureau is almost as high up as we get in the Empire’s chain of command. The only official higher on screen is Colonel Wullf Yularen, a Death Star background player from A New Hope who was reintroduced into the Clone Wars as an admiral in the Old Republic. Andor, as a show, is interested in the structure and form of state power, but it is a show savvy enough to know that it can illustrate that power most effectively by focusing squarely in the middle of its execution.

Partagaz becomes the chief surrogate for the Emperor, and in Episode 4 he offers the show’s most explicit thesis of Imperial Governance.

“Security is an illusion,” says Partagaz. “You want security, call the Navy, launch a regiment of troops. We are healthcare providers, we treat sickness, we identify symptoms, we locate germs, whether they arise from within or have come from the outside. The longer we wait to identify a disorder the harder it is to treat the disease.”

It’s language that is not that hard to imagine on CSPAN in the mid-2000s, or over happy hour drinks in DC in 2012. While the Original Trilogy predates the War on Terror, it is a set of films at a minimum in conversation with insurgency warfare. The Prequel Trilogy, too, is clearly inflected by the War on Terror. The Clone Wars, which launched in 2008, is invariably shaped by War on Terror narratives, especially when seen against the epic/heroic template of the 2003 Tartakovsky Clone Wars cartoon shorts.

Everyone sitting in the ISB briefing room, which the delightful crew of the A More Civilized Age podcast described as a sadistic graduate seminar, is operating from the position that Imperial rule is good and necessary. These are also security bureaucrats, so while there may be people in the galaxy who see autonomy and self-determination as long-term more stable than toggling up repression, none of those people are in the room where Partagaz explains his purpose.

As a prequel narrative, we know in advance broadly where it all ends up. Mon Mothma, running a masterful high-level game as a quietly radicalized but publicly marginalized liberal light, will be leading the Rebellion from Rogue One through Return of the Jedi. Cassian Andor will meet his end at the hands of the Death Star in Rogue One, his last biggest mission paving the way for rebel victory in A New Hope.

Seconds into the first episode of Andor, the show shows a date: 5 BBY. That’s five years Before The Battle of Yavin, a calendar that anchors events in the universe around the fixed point of the first Star Wars movie. We know, from the title and the convention, where this will all lead, even as the characters make their way through the rigor of hardscrabble life without any awareness of destiny.

High level strategy moments, like Partagaz explaining doctrine, are common throughout the canon of the universe, where stories often focus on the machinations of the powerful. Andor’s great success is showing that power as a structure, built from and in a material world. Every character is acutely aware that they live in Empire, even as they strive to ignore, endure, uphold, or overthrow the power around them.

It is what makes the Death Star in this show so haunting, even as we know it’s a threat ultimately vanquished. How could the Empire so comfortably destroy a planet unless they are inherently evil, Star Wars asks. In Andor, that’s complicated, though the evil of the action is never in dispute. Andor is a show about people doing their jobs, and in the Empire, one of the largest fields of employment is simply Imperial Functionary. The Empire can destroy a planet as a threat, because the Empire can turn an arbitrary police stop into a lifelong sentence in a prison factory. The Empire can destroy a planet, because its reaction to discovering a species that produces nightmarish screams upon death was to record those screams for a torture device, before exterminating the species as incompatible with Imperial rule.

What the Empire cannot see is what it is trying to erase. Andor not only grounds its characters in a material world, with concerns of debt and small-change payouts. It also grounds its worlds with rich and realized cultures, either tacitly tolerated by the empire or quashed through a forcible removal of non-Imperial sources of authority.

The Death Star is a promise that the answer to rebellion is fear, followed by extermination should fear be insufficient for neighbors to turn on each other. Thanks to a Thermal Exhaust Port that leads straight to the core of the space station, the Death Star arrives in New Hope flawed. Rogue One builds on that canon, telling a story of the flaw as deliberately designed-in sabotage, one last act of rebellion by an imprisoned engineer.

What is ultimately revealed, even if not spelled out as such in Andor, is that the Death Star is a structural flaw itself. It is a retribution weapon designed by an empire in a galaxy that lacks other sovereign threats. The rebellion that rises up and overthrows the Empire is made of Imperial subjects. The possibility that unrest could be responded to with anything other than an iron fist is alien to the Empire, and as the Prequel films and shows reveal, was ultimately alien to the Old Republic too.

Early in Andor’s final episode, as the various players make their way to an inevitable confrontation at the town square in Cassian’s adopted homeworld of Ferrix, Cassian listens to the rebel manifesto bequeathed to him by the late insurgent Karis Nemik.

“Remember this: Freedom is a pure idea. It occurs spontaneously, without instruction. Random acts of insurrection are occurring constantly throughout the galaxy. There are whole armies, battalions that have no idea they’ve enlisted in the cause. Remember that the frontier of the rebellion is everywhere, that even the smallest act of insurrection pushes our lines forward,” says Nemik.

Nemik writes in a philosophical language rooted in the tropes of natural law, in appealing to an authority that transcends the built edifices of states. He never mentions the Force, the actual supernaturally powerful force inherent in the Star Wars universe, though it is easy to read the Force into what he describes.

“Remember this, the imperial need for control is so desperate because it is so unnatural. Tyranny requires constant effort. It breaks, it leaks, authority is brittle, oppression is the mask of fear,” Nemik continues. “Remember that, and know this, the day will come when all the skirmishes and battles will have flooded the banks of the empire’s authority and then there will be one too many. One single thing will break the siege. Remember this: try.”

Nemik’s speech is, astoundingly, not even the most compelling case made for rebellion in that episode. It offers the notion that much as empire is an ideological project pretending to be a fixed law of the universe, so is resistance and rebellion. Star Wars canon, by constraint of timelines, needs for the Emperor to come into power 19 years before A New Hope, for that power to have been built comprehensively yet still feel insecure enough for a Death Star to make sense.

Andor does not answer the questions of what governance the rebellion will offer, though for the first time we really get a glimpse at a broader ideological program than just imperial overthrow. What Andor does, instead, is show that order and rebellion are shaped by the material of life, the conditions inherited and experienced by those who will make history.

In this reading, the Empire isn’t just an engine of evil constraining the galaxy. Empire is also a structure of evil, maintained by people who show up for work, send each other memos, and manage violence as it suits their career goals. For Tarkin, as for Partagaz, doctrine of Imperial Rule isn’t the best answer, it’s simply the only answer. It’s also why they both lost.

For the first time, we have seen a Star Wars truly focused on life under imperial conditions, of how such order collapses into rebellion. While the sequel trilogy adamantly refused to address questions of setting, much less history and governance, Star Wars is a setting that has room for stories about building in peace, against the constant specter of violence.

To get there, Star Wars would need to take the fall of the Empire as seriously as the fall of the Republic. There are rich stories in postwar just as there are in the prelude to war, and as Andor’s treatment of material conditions shows, those stories can be told in the ashes of the Tarkin doctrine, of the Partagaz prescription, and likely even in the inadequacies of Nemik’s manifesto.

Thank you for reading! I’m delighted to be back in the swing of things, and have been meaning to get this piece together ever since I saw the last episode of Andor. I should explicitly say that my thinking is heavily influenced by the deep, thoughtful, goofy and compelling conversations held by Rob Zacny, Natalie Watson, Ali Acampora, and Austin Walker of the A More Civilized Age podcast.

If you’re a new reader, welcome! I promise it will not always be Star Wars, though this will sometimes be Star Wars. I’ve got plans for revisiting an ancient project of mine about pundit accountability soon, and I’ve always got ideas that don’t quite fit my regular beats but are perfectly at home here.

As I mentioned last letter, I will be restarting payments on January 2nd, 2023. No hard feelings if supporting this letter is no longer in your budget or interests. If you do stick around or haven’t subscribed before and have a few dollars to spare in your budget, know that I really appreciate the support I get from readers directly. Thank you, and I look forward to writing for you more in the future.