In The Grim Darkness Of The Cinema, There Is Only World War II

On Star Wars, War Tropes, and what it means to forever be in the cinematic shadow of the One Good War

There’s a mortar in the latest episode of The Mandalorian.

It’s a minor point, one of multiple weapons wielded by the still-uniformed soldiers of the supposedly vanquished Empire as it conducts precision strikes out the outskirts of governed space. The mortar’s persistent menace is dramatically overshadowed by a couple of stormtroopers setting up a crew-served laser machine gun, and all of this detail is easy to miss in the background of the greater stakes of the space-fantasy fight.

For a moment, though, the mortar stands out. The scale of the combat is small: a dozen against three, until it is two dozen against three. And the terrain, apart from the fantastical centerpiece, is familiar enough to a rendering of modern war. It’s rocky and scrubby, with lots of cover, more climbing than running, and long-range weapons at a premium. If you squint, the multiple shuttle-like spacecraft even resemble V-22 Ospreys, the tilt-rotor transport iconic to the wars of the United States in the 21st century.

The mortar, a familiar form though rare for the franchise, is the kind of technology that shapes the contours of modern war. It bypasses cover, it hits at unfavorable angles, it is simple and cheap and carried by a person or two, and it represents the kind of iterative technological design that is part of a broader transformation in the way people kill each other.

Star Wars, by design and by tropes, lacks technological innovation in a meaningful way, with the single exception of planet-destroying laser weapons. To the extent that any of this matters for the overall war-and-weapons beat (debatable!), it matters because it constrains the contours of cinematic war to the familiar and the believable.

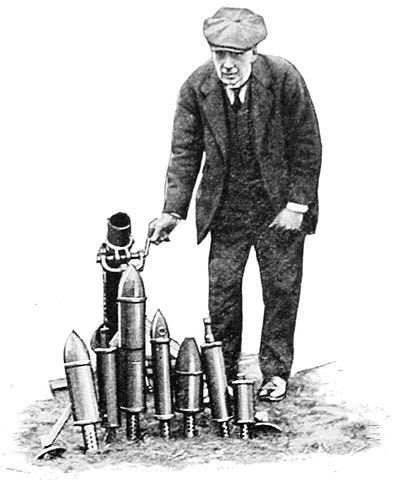

The mortar, despite its relative rarity on screen, is fully within the established tropes. For years, my business card included an old Popular Science illustration of the 1915 Stokes Mortar. It, like the swivel-mounted heavy machine gun, is a World War I staple that saw expanded use in the decades after, and especially in World War II.

All combat in Star Wars, everything bigger than a duel and up to and including fleets of space ships, is tied not just to the rules of how World War II was fought, but how World War II could be filmed. Those limitations have paid out incredibly well in giving the films (and, to a lesser extent, TV shows and video games and books and comics) fighting that feels both futuristic and familiar. It is easy to establish tension, to have sweeping movement and clear sides.

There is, among the broader national security community, a sort of soft consensus that of the five Star Wars films made since Disney bought the franchise, Rogue One is the standout. It is, equally, the least reliant on Jedi, and the one that is heaviest on World War II tropes.

But Rogue One isn’t really a World War II story, at least not as they’re conventionally told. It is, at the risk of stretching analogy to a breaking point, the Spanish Civil War but shot as though it's D-Day.

(Important caveat right away: debating what flavor of studio-produced Cambellian space-violence most aligns with any set of values means operating in a political spectrum so constrained it can fit on the head of a pin. I realize acknowledging this undermines all the rest of what I’m about to say, but I’d feel even sillier not doing so.)

The Spanish Civil War is perhaps over-mythologized by internet leftists and under-mythologized by everyone else. It is remarkable that, as the War on Terror saw a deluge of “fight them over there so we don’t have to fight them over here” shallow arguments, none of the war-debating types in DC turned to the actual war against fascism in Europe before World War II as a metaphor.

Instead, in the long window between the first Iraq War and the election of Trump, the various hawks of the Potomac would wonder aloud if this was a “Munich Moment,” after the 1938 conference in which Czechoslovakia, at the urging of France and the United Kingdom, ceded some territory to Hitler’s Germany under the promise and assumption that it would be enough to calm his territorial ambitions. That it wasn’t still discounts the status of rearmament in Europe at the time, which meant a war in 1938 was no more likely to succeed than the one in 1939. More importantly, the 1938 Munich conference had no bearing on anything related to Iraq in 2002, except that the Bush administration really wanted to be seen as the good guys going to war, and leaned super heavily on a historical memory of the United States as a military greeted as liberators in order to sell the war.

It helped Bush that his invocation of World War II came on the tail-end of a decade steeped in a revisiting of the war, of leaning into the Greatest Generation as a foundational myth of a longed-for lost unity.

“The pining for the glory days of the Good War has now been largely forgotten, but to sift through the cultural detritus of that era is to discover a deep longing for the kind of epic struggle the War on Terror would later provide. The standard view of 9/11 is that it "changed everything,”" wrote Chris Hayes in 2006. “But in its rhetoric and symbolism, the WWII nostalgia laid the conceptual groundwork for what was to come--the strange brew of nationalism, militarism and maudlin sentimentality that constitutes post-9/11 culture.”

In 2018, cartoonist Mike Dawson adapted Hayes’ essay into comic form, with a special emphasis on the cinematic underpinning of this World War II nostalgia. (The adaptation is not without its detractors).

Star Wars features in neither telling. The franchise spent the 1990s exploring the difficult task of post-Imperial reconstruction in books and comics, retelling the saga in video games and special re-releases, and launching a prequel trilogy. The politics of the prequels are unsubtle, and their timing in the Bush era was received as bold critique. It is hard to tell the story of democracy ossifying into Empire without invariably invoking the United States at its most actively hegemonic.

Rogue One has at least as much in common with Saving Private Ryan as it does the rest of the franchise to which it belongs. The climactic third act, with a patched-together grouping of fighters and specialists on a long-shot mission against a powerful foe, breathes the same beats as The Guns of Navarone or Bridge Over The River Kwai. While other modern films have leaned hard on ahistorical Higgins-style landing boats for their D-Day analogies, it is enough that the crew in Rogue One start their fight on a beach, and must scale a summit beyond it.

There’s crewed weapons and single-seat fighters and tank-esque vehicles and reinforcements and commandos and machine guns. There is, as best I can tell, no mortar, but there is a bazooka. The tropes, the feeling, is enough to make it feel, for a moment, like Michael Bay’s Pearl Harbor but in Space.

Yet the story of Rogue One, bound by the genre as it is, is not any Greatest Generation narrative. It is not a story about soldiers with futures. It is the Star Wars most focused on characters as insurgents, coordinating with other insurgents, in a fight that seems impossible to win but just all the same. Given how much Disney-era Star Wars has actively avoided a top-level view of the victorious New Republic, it’s something that its most triumphant film features characters who do not live to see victory, and who would be written out of history by the victors as soon as there was time to write history.

There is a messiness to Rogue One, from the assassinations to the jailbreaks to the diffuse cells of rebels and the use of torture, that makes it feel more like a civil war than, well, the Galactic Civil War at the center of the original trilogy. It is a story about insurgents, about irregulars, bound into action out of a vague ideological notion that an oppressive world can be made less so through a careful application of violence. (Solo, for all its faults, offers a complimentary set of worker revolutionaries to Rogue One’s political revolutionaries, though the grim fate of the uprising in Solo is left off-screen).

It’s a message that isn’t exactly an easy sell, so it gets the beach landing and the big speeches and the saccharine ending. It gets told as though this was the seamless prequel to A New Hope. Likewise, the Spanish Civil War gets discovered by students as a prequel to World War II, who can read history in reverse and assume that the sacrifices in Madrid and at Ebro were directly avenged by the conflagration that followed.

There’s a trope, common in the Trump era but perhaps never more than in the weeks leading up to the election, that slaps the label “antifa” on the soldiers landing at D-Day. It is, at best, well-intentioned. It is good to see fascism as the mortal threat that it is, and to side with the people drafted to fight fascism.

It is, though, a limited understanding of politics, of how holistic the work against fascism is. (It is especially grating when paired with a focus exclusively on voting, without looking at the formal and informal mechanisms that prevent facists from mobilizing in streets or executing power in government.) It misses what antifascism meant as an ideological project, rather than an incidental feature of a broader war.

“It was in the US contingent of the International Brigades, the Abraham Lincoln Battalion, that the first ever racially integrated American fighting force was born, commanded for a time by a black officer (by contrast, the US army remained segregated throughout the Second World War),” writes Helen Graham in her review of Giles Tremlett’s “The International Brigades: Fascism, Freedom and the Spanish Civil War.”

Including the Spanish Civil War from the start in narratives about World War II makes it harder to tell clean narratives about the Greatest Generation. For material that wants to reference either, it’s easier to lean on the tropes of World War II. The tech is similar enough, anyway.

The mortar (remember when this was about a mortar?) and the long rifles give continuity from the trenches of World War I to the Forward Operating Bases of the Forever War. At a small enough scale, down to a couple dozen people, much of war has remained familiar enough that specific tropes become universal.

The Mandalorian expands these tropes to tell, not the story of a war or an insurgency, but of the least-explored time in the modern Star Wars canon: the post-Imperial reconstruction. It is too early to see if this portrayal will lend anything more than a novel backdrop, but it has, at a minimum, offered something else valuable: a clear reminder that the armor of the Empire is supposed to invoke villainy.

Wars are violence attached to political meaning. Divorcing the symbols of violence from the purpose to which they were bent isn’t just bad politics, it’s bad storytelling.

It’s a memo not quite everyone has received.

I very much enjoy writing like this, and reader support is what lets me take it from a weird, time-intensive hobby into part of my patched-together freelance income. Paid subscribers can comment on all my entries here, and I’ve included a survey in my paid posts so I can better respond to what it is that subscribers actually want me to cover.

If you enjoyed this particular newsletter, or remember my (now-ancient, in internet time) work on Grand Blog Tarkin, let me know! My plan is to stick to mostly real-life war commentary for the newsletter, but I’m obviously happy to explore this space over and over again, too. If you are really, really interested in hearing me say more about Star Wars, for two years now I’ve been co-hosting A People’s History of the Old Republic, and you can dive into our audio archives wherever you get podcasts.

That’s all for this fortnight. Thank you all for reading, and if you’re in the mood for more newsletters, may I recommend checking out what we’re doing over at Discontents?

This was fantastic and got me to slam that Subscribe button. Just...damn.

I have a not uncommon pet theory that the initial first arc of the film was probably planned to feature Saw Gerrera with greater depth but that it was cut back in editing. Even as is, that first arc does end up intermixing ideology some with religion in a way that felt more contemporary.

I suspect the WW2 fixation is reinforced by studios often get squeamish about more recent wars that remain controversial. In return of the Jedi, I believe Lucas is on the record as going for Vietnam parallels, though work with locals against evil empire only goes so far in exploring that theme.