As best I can tell, the first reference to a future war in Popular Science comes in April 1896, nestled between articles on tropical fruit trees and X-Rays. In a long essay on “War and Civilization,” Canadian civil servant William Dawson Le Sueur sought to imagine a coming end to war.

Since its first publication in 1872 until Le Sueur’s essay, Popular Science had kept its thinking on war firmly grounded in the past or the present.1 The technological changes that are coming to shape war, the kind of machines that Popular Science will cover in depth over the next century, are not linked to any understanding of war as a specific phenomenon.

Which is what made Le Sueur’s essay stand out. Before he outlines why he thinks war is trending towards an end, he covers his bases thoroughly enough to anticipate a whole range of future conflicts.

“To say that war between civilized nations is henceforth impossible would be to speak with singular rashness,” Le Sueur writes, “in view of the vast and ever-increasing preparations for war which the most civilized nations have, during the last ten or twenty years, been engaged in making, and in view also of the waves of warlike sentiment which have lately swept over communities that might be supposed to be by instinct and principle most inclined to peace.”

Published in the April 1896 issue, Le Sueur’s “War and Civilization” is a normative argument. It looks at the growing body of laws of war and treaties limiting conflicts as a sign that restraint will triumph over violence. The piece is specifically structured as a rebuttal to “On War,” an 1853 essay by British reactionary nationalist Thomas de Quincey.2 I’m less interested in reviving discourse from centuries past than I am about seeing what, if anything it foretold in the present.

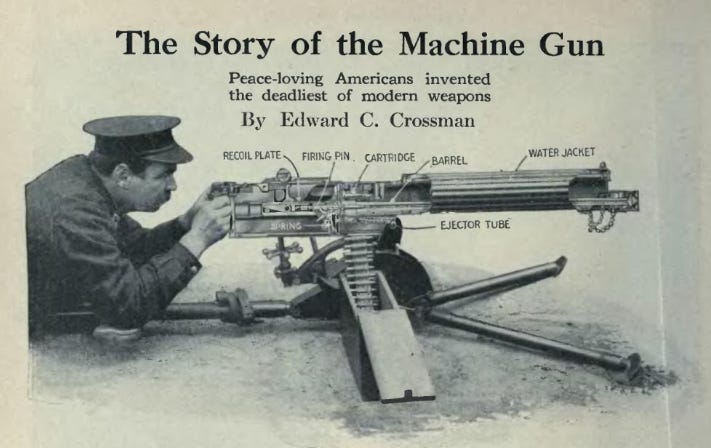

Le Sueur, writing after the advent of the Gatling gun3 but before the epoch-defining violence that would shatter illusions of civilization in blood-filled trenches, pointed to modernization as a way to humanize war.

“It is acknowledged on all hands that the character of war has changed greatly for the better in modern times,” writes Le Sueur. “It still is a matter of killing and of maiming in the endeavor to kill; but, decade by decade, it has to reckon more and more with the spirit of humanity.

As I wrote last summer, the eponymous Gatling did more than almost anyone to turn technology towards mass slaughter. Concerned for his legacy, he wrote letters saying it would reduce the exposure to battle for many, and was thus ultimately a humanitarian concern.

There’s one last line from Le Sueur I want to share. Surprise attacks, here romanticized by de Quincey as primal “glaring eyes,” are a danger Le Sueur acknowledges as threatening the calm rational calculus of war that he imagines constrains modern nations.

Yet, he says, the weapons of war may someday become so terrible that the violence in the moment of surprise is cataclysmic itself.

In a phrase that anticipates nuclear war as much as anything I have ever seen pre-1945, Le Sueur writes “what woe it would be if a moment’s madness should mean the wrapping of a kingdom or a continent in the flames of war!”

II

I don’t know if I would have found anything remarkable about Le Sueur’s essay had it not been in Popular Science. Certainly, the line about a moment’s madness wrapping a “continent in the flames of war” is evocative, and I am glad that I found it.

What makes the essay for me, though, is how it sits inside the legacy of a publication that will be 149 years old this May. Enthusiast press is rarely legacy media. Few publications can speak from that length of coverage, with an archive as rich and flawed as the whole span of history from the 1870s to the present.

When I write about machines of war, I try to keep in mind not just the people who will read it today, but how my glib description of an autonomous missile will play in a year, or a decade, especially after its “kinetic potential” has been realized in a human tragedy, an innovation measured in blood.

There is not, generally, a lot of follow-on journalism when it comes to new machines of war. One of the reasons I think the F-35 has become so salient a symbol of military excess is because it has endured long enough as the only fighter of its kind to really support a thriving industry of follow-on stories.4 Most flashy robot projects, new missiles, smart bombs, military data tools? If they hit the popular press, they hit at their debut, and then fade away.

Weapons, in the enthusiast press today, exist always in a future tense, or at least a tense future. By the time the weapon is a tool of routine violence, the enthusiast press has mostly moved on.

I set out to find an early instance of future war speculation to see if that was always the case. Le Sueur’s entry is so strange relative to the shape of technology journalism to come that it is hard to say how, exactly, how it fits in. I imagine this will be an ongoing search, something I slot into my regular writing about more-current machines. I love learning about the history of my beat when I can, and so long as I have readers here, I am happy to take you along on the ride with me.

Less than twenty years after Le Sueur held up (European, Christian, white) civilization as a force against war, europe carved itself apart with explsives, and then filled the wounds with barbed wire, mud, and bodies rendered inert by the deadly children of Gatling’s terrible machine.

A little bit of, er, personnel news.

A few weeks ago, I changed up my mix of existing freelance projects, and started contributing to Popular Science again. I’m six stories in so far, and greatly enjoying it. I wouldn’t be in this field at all were it not for a generous trial and start at PopSci back in February 2013, and there is something about this venerable-yet-accessible little publication that speaks to me. I hope I get to keep writing for it for a long time, or, failing that, that I can always return to it again.

Wars of Future Past will remain part of that freelance mix for me, though I am increasingly ambivalent about how I feel about having Substack as the home for this work. I’ll let you all know before I make any changes, but I want to be upfront that I’m thinking about it.

Thank you all for reading. At some point this year, I’m going to send a survey asking for more information on how I can better serve you. You are the audience I most enjoy writing for, and I want to know what I can do to ensure that these newsletters are serving you at least as much as they are serving me.

If you’re in the mood for more newsletters, may I recommend checking out what we’re doing over at Discontents?

Google Books, which holds every issue of Popular Science in its archive, has a surprisingly limited search function, and as such it's entirely possible I missed a reference in the archives to future war from before 1896. A search through Hathi Trust’s archive confirms there are many entries dealing with historical wars and present wars, as well as more philosophical observations on Science and War.

Between his ideological orientation and the fact that De Quincey is also broadly credited with the modern drug memoir, he’s basically the Wario version of Hunter S. Thompson but a century earlier.

Gatling guns show up at least twice in the archives of Popular Science before 1896. I saw one entry using Gatling as a metaphor for how plants disperse seeds. Another lists him among several inventors who had their start in the South but moved away before finding success.

The single best of these remains my former Defense News colleague Valerie Insinna’s entry for The New York Times.