CHIPS Fall

Revisiting Biden's "Arsenal of American Prosperity"

Edited by Althea May Atherton

This is a story about writing a story.

In November 2020, shortly after the Presidential election was decided, I sent a pitch to a publication about the way Biden might lean on the war industry for stimulus that could get through a divided Congress (this was before the Georgia elections that formally gave the Democratic party control over the Senate).

Here is that pitch (with the name of the publication removed):

The Great Power War Stimulus

With a Green New Deal likely off the table, to say nothing of reducing the Pentagon's budget, government stimulus spending is likely to come through building up a more modern "defense industrial base," designed to spur domestic production of everything from 5G to microchips. There are already amendments with bipartisan to this effect in the NDAA and otherwise, but what I think is especially keen for [your] audience is the weird role of, like, nationalism and industrial policy, an uncomfortable future of "the federal government can spend money on jobs, but only if it's premised as for a war against China."

As I often do, I teased my story idea in tweet form:

Five days after pitching, I handed in the first draft, titled “The Iron New Deal,” and over the course of the next few months went back and forth on edits, with the publication ultimately deciding not to run it. With permission, I pitched the story to a second publication in January 2021, this time with the Democratic Party in control of the Senate, if only by the thinnest margin.

I pitched the story as “Biden And The Arsenal of American Prosperity,” with a subhead that read, “While Democratic dreams of a Green New Deal fade, a new stimulus may draw inspiration from the second half of FDR’s legacy.”

That draft also underwent a couple months of edits, as well as a title change, and eventually I asked the editor to let me run the story at Wars of Future Past instead. Now in the position of publisher as well as writer, my once-obvious clarity on when it made sense to run the piece vanished, and I’ve been sitting on it ever since.

The high-profile effort by Congress and a whole swath of industry to pass the CHIPS Act of 2022 brought it back to the forefront of my mind.

Congress moves glacially until it moves all at once. On July 28, 2022, the House passed the CHIPS Act, which had already cleared the Senate. When I started writing this draft of the newsletter barely over a week before, the text of CHIPS was hard to find, and now it may become law in the hours between when I schedule this newsletter and you read it. The bill, as passed, contains over $52 billion for semiconductor manufacturing in the United States.

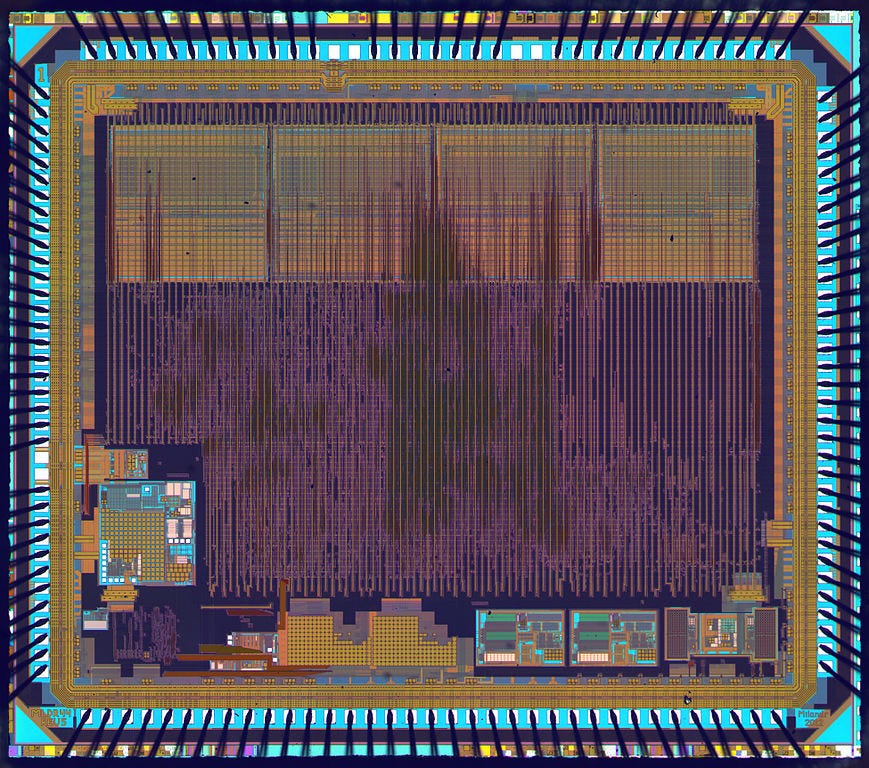

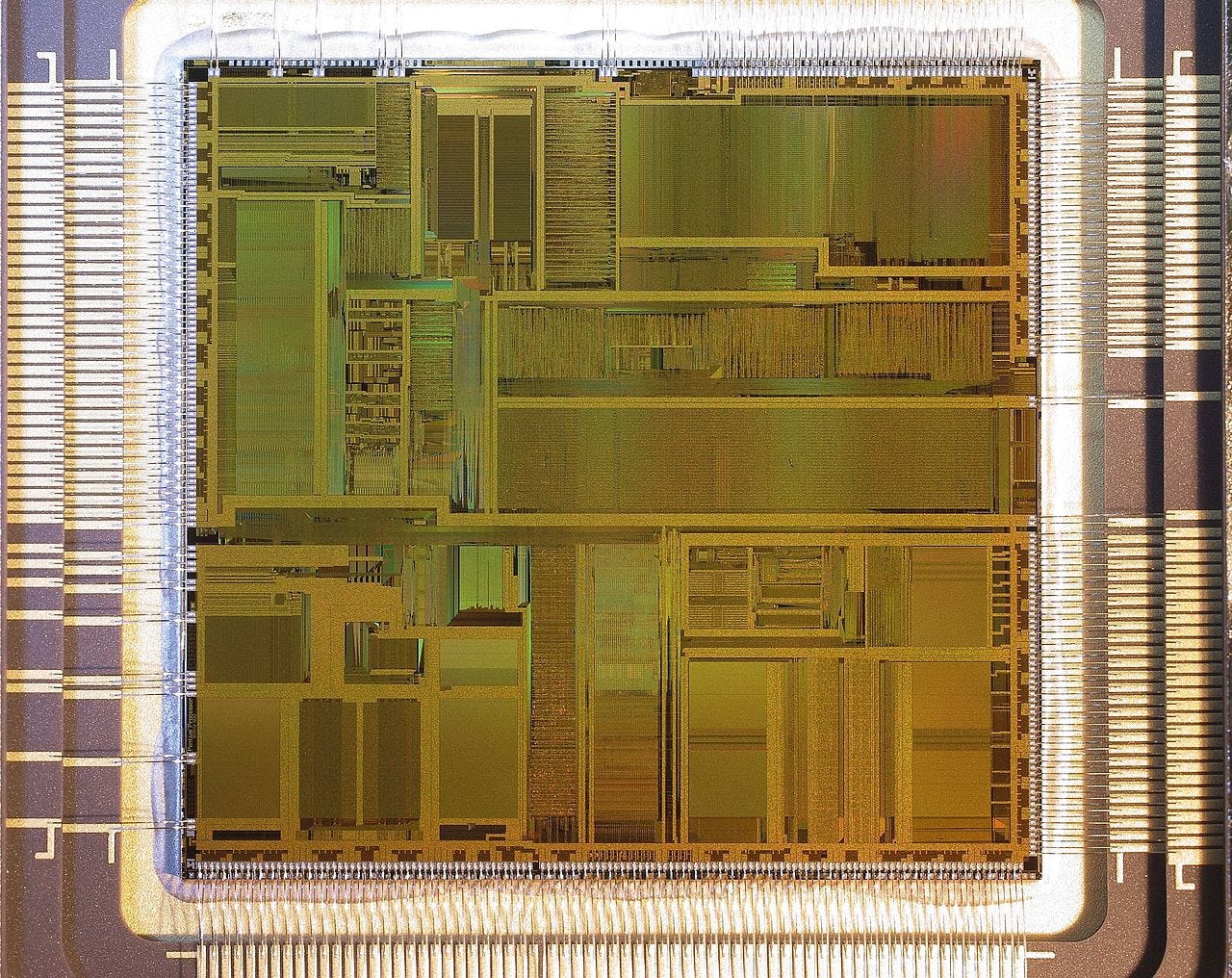

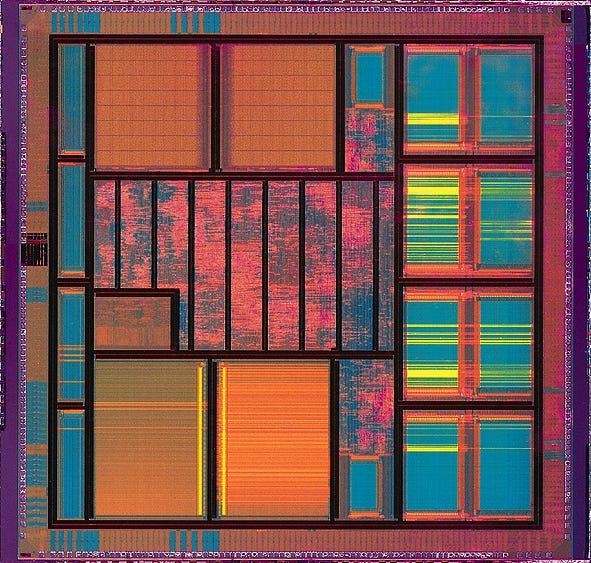

In the summer of 2020, I wrote about an earlier act by a similar name. The “Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors for America Act”, or “CHIPS for America Act,” was industrial policy to create domestic US production of semiconductors in the name of national security. It’s a business-heavy story. Despite my career covering new and emerging technologies, I have tried hard to be a military technology reporter without actually being a business reporter.

But in the summer of 2020, I was covering technology for Breaking Defense, so I wrote about the specific bill. That story was about what it meant that otherwise-principled opposition to direct government spending on creating industry fell away if the expense could be justified as national security.

It was this impetus that I turned to for “The Arsenal of Prosperity,” imagining that in place of the Democratic left’s desired Green New Deal, Biden might instead push for stimulus similar in scale but far more militaristic in intent.

Here is that story, lightly edited since March 14, 2021. I’m running it here as a frozen time capsule of how I was thinking about stimulus and industrial policy at the dawn of the Biden administration, before two years of vanishingly little congressional action.

The Arsenal of Prosperity

As the drones swarmed over President-elect Biden during his victory speech on November 7th, it was easy to imagine, if only for a moment, that 2021 might again usher in an age of technical marvels. “What is our mandate?” Biden asked, and answered, in part: “To marshal the forces of science and the forces of hope in the great battles of our time.”

The actual battles fought by the United States, with drones and missiles and 20-year-olds, went unmentioned in the speech. In part, it’s the length of the Forever Wars - now into their fourth presidency, and more than old enough to vote — that makes them so invisible and so normalized. But at the dawn of a new presidency another great battle is brewing: a Cold War with China, fueled by a bipartisan mantra to “buy American.” More federal money is set to be pumped into the security state, but this time with the explicit intent of creating middle-class jobs.

Both Jake Sullivan, Biden’s National Security Advisor, and Salman Ahmed, director of Policy Planning at the State Department, were coauthors on “Making U.S. Foreign Policy Work Better for the Middle Class,” a report that called for, among other things, a “National Competitiveness Strategy” to make workers more competitive in the global economy.

Every year, Congress passes a National Defense Authorization Act to fund the military. Because it is almost always guaranteed to pass, the bill serves as a benchmark of where, exactly, the parties agree, even in divided government. This year, both Senate and House versions of the NDAA earmark $6 billion specifically to counter China, though the approaches vary: the House version includes money to put missile defense systems on Guam and to pay for military exercises with allies. The Senate version would spend that money fortifying Pacific bases, and moving fuel and missiles closer to China.

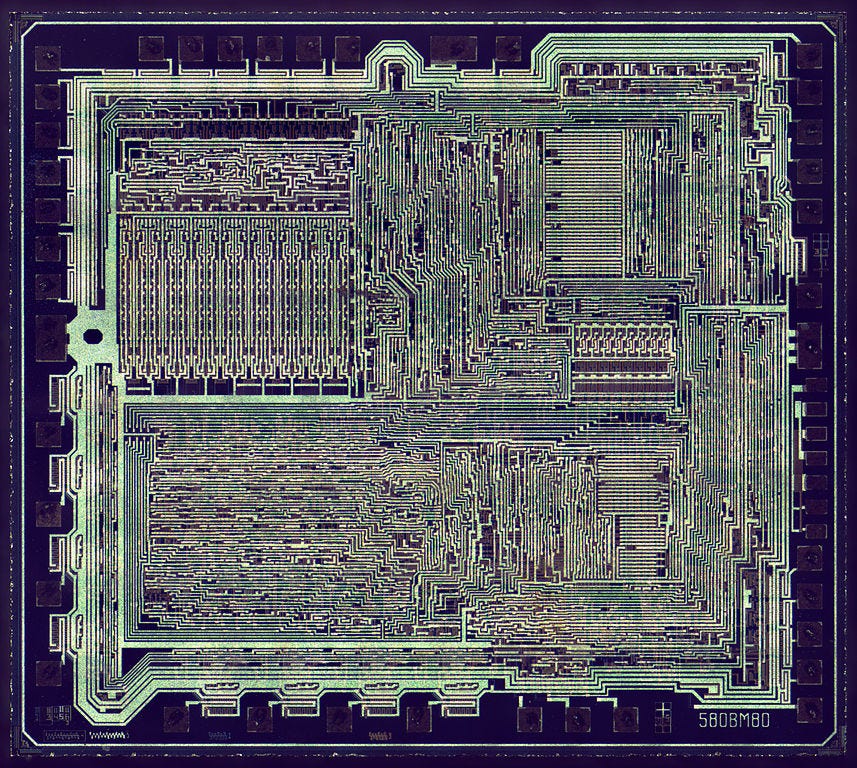

Yet the real shift in the NDAA is a bill that wants to counter China not with weapons, but with factories—for manufacturing weapon parts. The Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors for America Act, or the CHIPS For America Act, was introduced in June [2020] by Republican Senator John Cornyn, and co-sponsored by Democratic peers like Mark Warner and Krysten Sinema. A parallel version was introduced in the House, and complete with acronym intact, the bill is now law through the NDAA.

As authorized, CHIPS will allocate $10 billion of federal spending to build a domestic semiconductor industry. CHIPS is explicitly “industrial policy,” in which the federal government funds a desired kind of industry into being.

The money in the CHIPS Act would go to everything from electronics research at DARPA and the Department of Energy to creating a Manufacturing Institute to produce semiconductors, which are used in everything from sensors to computers to navigation systems on missiles. That’s a particularly sensitive area because roughly two-thirds of the global semiconductor industry is in Taiwan, China’s democratic neighbor and a U.S. ally - and a country repeatedly threatened with invasion by Beijing.

Industrial policy is not new.

As Jared Bernstein, a former economic advisor to Biden, put it in Foreign Policy in July 2020, industrial policy is “the idea that in pursuit of a national goal, the government can and should choose particular industries for targeted help—which can take the form of low-cost loans, grants, subsidies, tax breaks, or direct purchases of goods and services using the government’s $600 billion annual procurement budget.”

The exact nature of the spending is somewhat secondary to the fact that spending is happening at all, though some kind of direct payment is usually crucial to make an industrial policy stick. While Bernstein specifically referenced industrial spending in the context of a Green New Deal, his argument was far broader. Rather than pretending the United States does not use its spending to pick winners it thinks are important, the government should be explicit, and make the case for how government spending benefits the nation as a whole.

“As long as the United States has been a nation, it has implemented industrial policy just like every other country, and it will continue to do so. The United States might as well get it right by being transparent and smart about these policies,” wrote Bernstein.

While the fate of progressive policies like the Green New Deal hinges on how they can be specifically sold to Joe Manchin, the conservative Democratic Senator who now represents the margin necessary to barely pass measures in the Senate, industrial policy is likely alive and well, provided it can disguise itself as national security. Building industry to defeat China in the market and, possibly, in a future war could replace action on climate as the animating spirit of Biden’s industrial policy.

The CHIPS for America Act is motivated by equal parts fear and nationalism (charitably, national security): The fear is that the United States, without its own controlled supply chain, will lose access to electronics it needs, either because China specifically stops selling to the US, or because of Chinese invasion or coercion of other countries in Asia, making then unable to sell to the US. Decoupling these supply chains means less economic dependence on China in peacetime, and in the event of a military conflict, would allow the United States to continue to acquire the specific supplies it needs to keep fighting. The economic damage involved in decoupling becomes an excuse for pumping money into preferred sectors in order to compensate.

At a virtual event promoting CHIPS this past July, Cornyn linked his support of spending federal money on industry to a deep concern that it was the only way to beat China in the tech areas where the U.S. had fallen behind, like 5G and semiconductor manufacturing. As I reported at the time, while Cornyn said his faith in the free market made him uneasy with industrial policy, he was convinced it was worthwhile to maintain American technological preeminence.

Biden’s campaign included a platform for industrial policy, using the language of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to outline future spending. Biden’s touchstone is not the FDR of the New Deal or the Works Progress Administration. Instead, it is the FDR of World War II.

“U.S. manufacturing was the Arsenal of Democracy in World War II, and must be part of the Arsenal of American Prosperity today, helping fuel an economic recovery for working families,” declared the campaign. “Biden’s comprehensive manufacturing and innovation strategy will marshall the resources of the federal government in ways that we have not seen since World War II.”

Roosevelt gave the Arsenal of Democracy speech in December 1940, as he prepared to build up American industrial capacity to sell weapons to allies fighting against Germany and Japan. While Biden’s “Arsenal of American Prosperity” platform lacks the military urgency of FDR, the platform references China almost 30 times, highlighting economic competition and technological development.

In a sense, Biden’s campaign [leaned] into industrial policy not because it anticipated needing the technology for a future war, but because it saw the economic competition between the countries as the actual fight.

Couched in the language of national security, paired with the right threat, and with the payouts marked for the right states, CHIPS shows that the parties have some overlap on where, exactly, they are willing to directly inject money to shape the economy. This is the likely shape of any non-Covid stimulus to come, if that stimulus needs to be authored by both parties in Congress. If Cornyn can support industrial policy under the banner of national security, it is likely Manchin and Arizona’s Krysten Sinema can, too. If the technologies themselves have civilian applications as well as military ones, then that’s an added bonus.

An industrial policy built on self sufficiency in the face of the growing military prowess of rivals is hardly unheard of. In fact, it’s one of the driving forces behind China’s own push for further national independence on semiconductor manufacturing. But direct investment in the private sector is not without consequences. The Trump administration regularly and recklessly used tariffs to shape the global economy, aimed at disrupting what it saw as unfair support of industries by governments abroad.

While it is less likely that a Biden administration would face tariffs from the rest of the world for funding industry, there are other potential consequences to pushing industry on the basis of a future war. In the short term, it likely means the US government paying more for products that can be found for less on the international market, and an emphasis on boosting industry instead of compensating Americans directly or taking the steps necessary to fight climate change. In the long term, it risks national cloistering of technology research, as a once-international pool of researchers become trapped in national struggles, and in further locking in a conflict that too many in both China and the United States already see as inevitable.

For another sense of how news moves slow and then fast, this section previously contained 300 words about how bleak it was that CHIPS is the high water mark of Democratic spending under the Biden administration and the Manchin Prime Ministry. Shortly after CHIPS cleared the Senate, the Democratic Party signaled movement on a brand new package of stimulus spending with a significant climate component, all couched in the Manchin-amendable terms of the “Inflation Reduction Act”.

There are other, better, thoughtful writers to read on what the act means, what its merits and limits are as a climate bill. For my purposes here, I will join the chorus surprised that anything not directly tied to a narrow understanding of national security was even on the table again. The bill still has to clear an evenly split Senate, with the looming threats of a Democratic defection, a Senate absent for Covid, or a ticking clock towards congressional recess. Such is the nature of the least democratic part of the national legislature.

I can’t begin to speak to the odds of the Inflation Reduction Act’s passage. But CHIPS is now all-but-law.

The machinery of war is the heart of my beat, and while the CHIPS act is certainly something for me to write about for years, it remains underwhelming that massive direct spending on chip manufacturers in the name of war is the Senate’s only unified vision for industrial policy in the age of climate change. Should the IRA pass, it will do so on the slimmest of margins, despite massive popular support for tackling the problems it is aimed at.

CHIPS is premised on the fear that domestic production can enable self-sufficiency during a war that disrupts supply chains for smart missile and sensor production. It’s a fundamentally pessimistic view of international politics, yet it’s the rare bill that sees a challenge of the 21st century and proposes active government action as a solution.

Thank you all for reading. I have been waiting nearly two years for that piece to finally see the light of day.

Althea and are very sorry that we ghosted you last month as we made some adjustments and big decisions, including about this newsletter. We have decided to pause Wars of Future Past payments for the month of August so we can migrate to Ghost, a platform committed to being a platform, not a publisher with an editorial line. We are looking forward to haunting your inbox via Ghost in September, 2022. If you have any questions or tips about the migration and/or you want to air any further grievances, please let us know.

If you have been missing me, I have been writing the Critical State newsletter from The World and Inkstick Media since March. At the center of each of those newsletters, I take a dive into recent academic work related, broadly, to foreign policy, and the archive of those newsletter essays can be found here. I think the newsletters stand on their own, but they also provide me with an experience every columnist needs: homework in which I read other better, smarter writers.

Thanks for sticking with Wars of Future Past, and I look forward to writing many more stories for y’all. As always, if you have any feedback, feel free to reach out to Kelsey at warsoffuturepast@gmail.com and Althea at athertongazetteer@gmail.com.

Thanks for the story around the story, in tune with the reach-around qualities examined.

I do think you missed an opportunity to connect House Speaker Nancy Pelosi's currently threatened visit to the Republic of China, Taiwan. As you point out Taiwan is the hub of global semiconductor chip production, and I think to see some correspondence between the Speaker's husband's investments in tech stocks like AMD, the Speaker's steely-eyed push of CHIPS, and Peolsi's hawkishness on China, all of which (and there may be one or two additional swirls in the nexus that I'm unaware of) sort of crystalizes with the idea of this article. The Taiwanese have been exploring and leveraging the tech incubator model of production for a good 30 years at least, and PRC China has reproduced this blueprint successfully in Shenzhen in a little over a decade. I'm not sure how savvy Pelosi (or the Pelosis) are on bootstrapping incubators, but 1) a US attempt to replicate the Taiwanese business model on our mainland would be interesting to say the least: wafer production is not an inherently clean industry, and tiny Taiwan has also been a pioneer in balancing production rates against emissions (then again they do have a literal sea at hand to piss and poop into), and 2) the US Big Software money, particularly Facebook-Meta with it's very hardware-based VR/AR ambitions (or desperations), want onshoring of semiconductor production to go well. But wafer foundries are not very Green, so there's some tension there, a can to kick down the road. Ty, D