A Time To Reaper, A Time To Swarm

Buzzing about the future of drone war as the AUMF enters its fourth presidency.

The state is an inheritance of violence. Sometimes literally, in the way that subjects, lands, and ministries were formally passed along monarchical lines. Other times there’s a mediating structure, built out of something late in the middle ages, designed with all the thrill and intrigue of a Cones of Duneshire built by a committee of extremely limited bourgeois radicals.

The presidency, and with it the American state apparatus, is such an inheritance. By design its institutions predate the office, and almost all of them, for any given presidency, will post-date it too. The state, especially the post-1947 National Security State, rarely shrinks.

What is particularly striking about inheriting the state in the 21st century is that the presidency comes with the same ongoing wars. When president-elect Joe Biden assumes the Presidency on January 20th, 2021, he will become the fourth president to oversee the US war in Afghanistan, and the third president to inherit it.

The 2001 AUMF, the short bill that authorized the war in Afghanistan back in 2001, has now been part of the American experience for half again as long as prohibition. I’ve already written at length about the weirdness of the length of this war. What I want to mention today, specifically, is how tech will shape increased state capacity for violence.

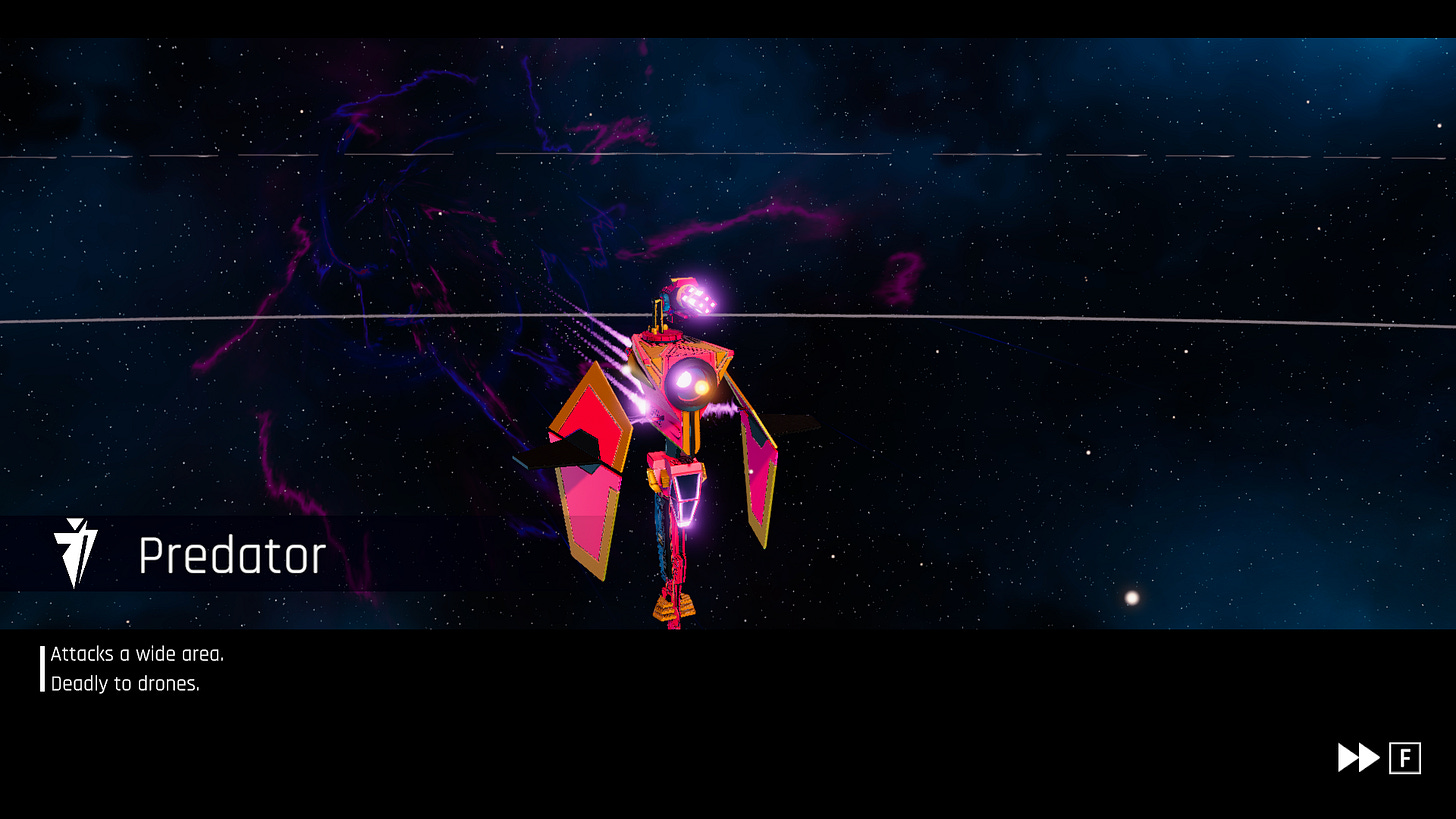

The Predators, which were first armed under Bush and are so linked to Obama-era policy, are mostly retired. The Reapers that replaced them have years left, provided the forever wars continue and skies remain as free from anti-aircraft weapons as they have in the past.

What will be new, when it comes to flying robots, will be an altogether different sort of machine.

Reaper-style drones are labor intensive. This is part of the reason the Air Force doesn’t like “unmanned aerial vehicles” as a term, even though there are no humans on board; drones are crewed, in shifts for the duration of their sometimes 24-hour flights, requiring more pilots and support staff than similar people-occupied aircraft.

If flying robots are going to be a labor-saving device, the machines will need to rely on human direction less. Reapers are directly piloted: a human sits in a console with a hand on a joystick, reading aeronautics information transmitted from the robot often thousands of miles away, and looking at video from on-board cameras.

There are parts of Reaper flight that are already autonomous. The planes can maintain cruising altitude and perform some navigation tasks on its own. But that is fairly standard for modern people-carrying aircraft, too.

To really reduce the amount of people involved in controlling a robot, the robots have to be managed, more than piloted. Waypoint navigation, where a robot flies on its own to paths set by a human, is a simple way to do this. Swarming, where many robots communicate with each other to understand how they relate to each other in the sky, and then perform tasks as a cluster, is another.

I saw two swarms this week, one warlike and simulated, the other real and peaceful. Let’s start with the war first.

Over at Vice, I reviewed “Drone Swarm,” a game whose plot is mostly forgettable and whose signature mechanic involves directing 32,000 flying robots in battle. I found the gameplay mostly tedious, because it involved a lot of hands-on controlling of robots, instead of finding ways to make that autonomy work for the player. It might be the game’s singular focus on one swarm that caused this tedium; other real-time strategy games, where players command a host of units, have for decades automated a lot of functionality, to make it possible for a single human player to manage hundreds of units at the same time.

The peaceful swarm, poetically, took to the skies about the Biden-Harris election victory party. Produced by Verge Aero, this swarm was a kind of light display, whose robots spelled out shapes and words and lit up in red, white, and blue.

I think drone swarms as pyrotechnic alternatives are super-neat. They can have the flash of a fireworks show without the noise and smoke, and the drones offer far more control over what actually gets displayed.

I also, though, cannot help but see the swarms of entertainment the way airshow goers in the 1920s may have marveled at the speed and agility of brand-new single seat monoplanes. Aircraft are dual-use technologies. The kinds of algorithms, controls, and sensor integration that make it possible for swarms to maintain formation while drawing an outline map of the lower 48 United States also inform design for flying robots with a far less spectacular purpose.

Russia, the United Kingdom, the UnitedStates, and others are already working on drone swarms for battle. There’s technical and legal hurdles, of course, and converting a largely static display into a weapon takes some effort. But drone swarm efforts of the United States are work that began in the last decade, continued through the Trump presidency, and will continue into the president.

Along with the legal apparatus authorizing war, Biden is set to inherit the whole of the American military enterprise, an incredibly polite euphemism for everything from in-the-works drone swarms to one of the two largest nuclear arsenals on the planet.

What remains to be seen, like so much else of this moment, fraught with possibility, is if the nascent worker resistance to building a war machine for the Trump administration will carry over to the Biden era.

CLOUD PHISHERMEN

Over at Breaking Defense, I wrote about NSA warning, North Korean hacking, and cloud-based browsing.

What has stood out about defense coverage like this, really, is how much the Pentagon process treated the Trump era as normal, and how undisrupted it will be following the election of Biden and, at most, parties at parity in the Senate. Asked to comment on the then-uncalled election on Thursday, defense officials were unwilling to make claims about their budget, only that they expected the NDAA to resolve at around their request. This was, I should say, in a call where the same official readily offered that a change in browsing offered savings of $300 million (3.6 F-35As) in future spending.

That’s a tremendous amount of money to casually toss around in conversation! I know that the Pentagon operates on a whole different scale than most anything else, money-wise, but it’s still staggering how much money that is. I hope I never stop finding it weird.

I very much enjoy writing like this, and reader support is what lets me take it from a weird, time-intensive hobby into part of my patched-together freelance income. Paid subscribers will gain access to more ways to directly contact me, and I’ve included a survey in my paid posts so I can better respond to what it is that subscribers actually want me to cover.

That’s all for this fortnight. Thank you all for reading, and if you’re in the mood for more newsletters, may I recommend checking out what we’re doing over at Discontents?