English historian John Richard Green declared the 100 Years War in 1874. French historian Jules Michelete beat him to it by 41 years, using the term in 1833.

The actual wars that encompass the (reductively named) 116-year span, fought on behalf of respective monarchs of what would become France and England over inheritance claims and feudal rights, was, centuries after its end, seen collectively as one longer conflict, spanning generations

Similarly, the 30 Years War of 1616-1648, is the modern catch-all for the array of proto-state violence that broke out regarding sovereignty and religious confessional status, and then escalated into a theater-wide struggle. Its popular understanding as such, into a tidy division of three decades, can in one strain be traced through an Italian novel, published in 1842. (Though it can be found earlier; an English paper called it the Thirty Years War in 1649, just a year after the halt of hostilities, which is a pretty bold time to stake out that claim!)

It is not yet clear how history will regard the long-running wars launched by the United States under the auspices of the 2001 Authorization to Use Military Force, but in year 19, there appears to be a soft consensus among foreign policy types in the United States for “The Forever War.”

Forever is an aggressively indefinite moniker, and its broader adoption comes from the failure of more overt branding efforts. The Bush administration, which launched the conflicts that have yet to end, used “The War on Terror,” itself borrowing language from “The War on Drugs,” America’s earlier foray into indefinite irregular conflict against a concept.

I can still recall the moment, spring semester 2009, in my War on Terror class when the newly inaugurated Obama administration renamed the War on Terror into “Overseas Contingency Operations.” I thought, naively, so naively, that this change to sterile language for an inherited conflict might precede an actual, durable change in policy.

It didn’t, and here we are, in the third presidency of an open-ended war against a broadly defined foe, with its end unforeseeable.

The endless nature of the Forever War was seen from the start, anticipated in countless places and among critics dismissed as pessimistic for years. On Twitter last week, I attempted a rough outline of the term’s origins, as specifically applied to the 2001 AUMF, working backwards from the present to settle on two main namesakes.

The more recent, and more durable, is, well, “The Forever War,” a book by war correspondent Dexter Filkins, published in 2008. Before that, in 2005, the New York Times magazine published an article by journalist Mark Danner, called “Taking Stock of the Forever War.”

There are other, earlier names that could have become the go-to term. The Pentagon itself called the Afghanistan part of the War on Terror “Operation Enduring Freedom,” which was ended in 2014 and replaced by “Operation Freedom’s Sentinel,” a name that conveys vigilance without even a hint at a timescale.

Before “Enduring Freedom,” the name was “Infinite Justice,” which would sound uniquely Rumsefeldian were it not also a reference to “Operation Infinite Reach,” the Clinton-authored cruise missile strikes on Al Qaeda bases in both Afghanistan and Sudan. Those strikes, notably, failed to kill future 9/11 planner Osama bin Laden, and also destroyed a pharmaceutical plant in Sudan, one without any ties to al Qaeda.

(Quick aside: while drones have dominated the discussion of the forever war, most of the same arguments about drones enabling directed violence took place twenty years prior, and were about cruise missiles. In both cases, a focus on the ability of a weapon to put an explosion on a dot on a map obscured the broader failures that go into knowing who, or what, exactly, will be on the ground when the blast hits.)

I’d be remiss if I did not, so late into this, acknowledge that, yes, “The Forever War” is a 1974 novel by Joe Haldeman. What is perhaps most relevant for an understanding of modern wars is that the conflicts continue, tangentially connected to the people they are nominally designed to serve. The war itself may be open-ended, but human lives are especially finite.

The 30 Years War, and the 100 Years War, stand in history in part because the specific are less important than the enduring nature of the violence. For most of the people not involved in the fighting, which is to say, always, most people at most times, war is a thing that happens to and around them, instead of something they actively decide to do.

Once people are under arms, and their leaders see gain through violence or peril without it, the war can perpetuate itself until the enemy is vanquished, the leader tires of conflict, or the capacity to wage violence is gone. In the United States in the Forever War, the enemy is by design unvanquishable, three successive presidents and nine successive congresses have yet to tire of the conflict, and the capacity to wage infinite war as a nation has hardly been diminished, even as the individuals doing the fighting have been burnt out, broken down, or retired.

It wasn’t exactly the term, but Hunter S. Thompson, in his column for ESPN that ran on 9/12/2001, said “We are At War now -- with somebody -- and we will stay At War with that mysterious Enemy for the rest of our lives.”

The Forever War doesn’t have to stay that way, but it will take people actively working in the halls of power, and outside them, to end it. With luck, the historians of the 2400s will look back at our own 30-year war (dating back to the start of the Gulf War, as Veterans Affairs already does) and see it as a unified blip before a couple centuries defined by fighting climate change. If we are unlucky, there may not even be historians in the 2400s, and we’ll have a myopic focus on terror, in part, to thank for that.

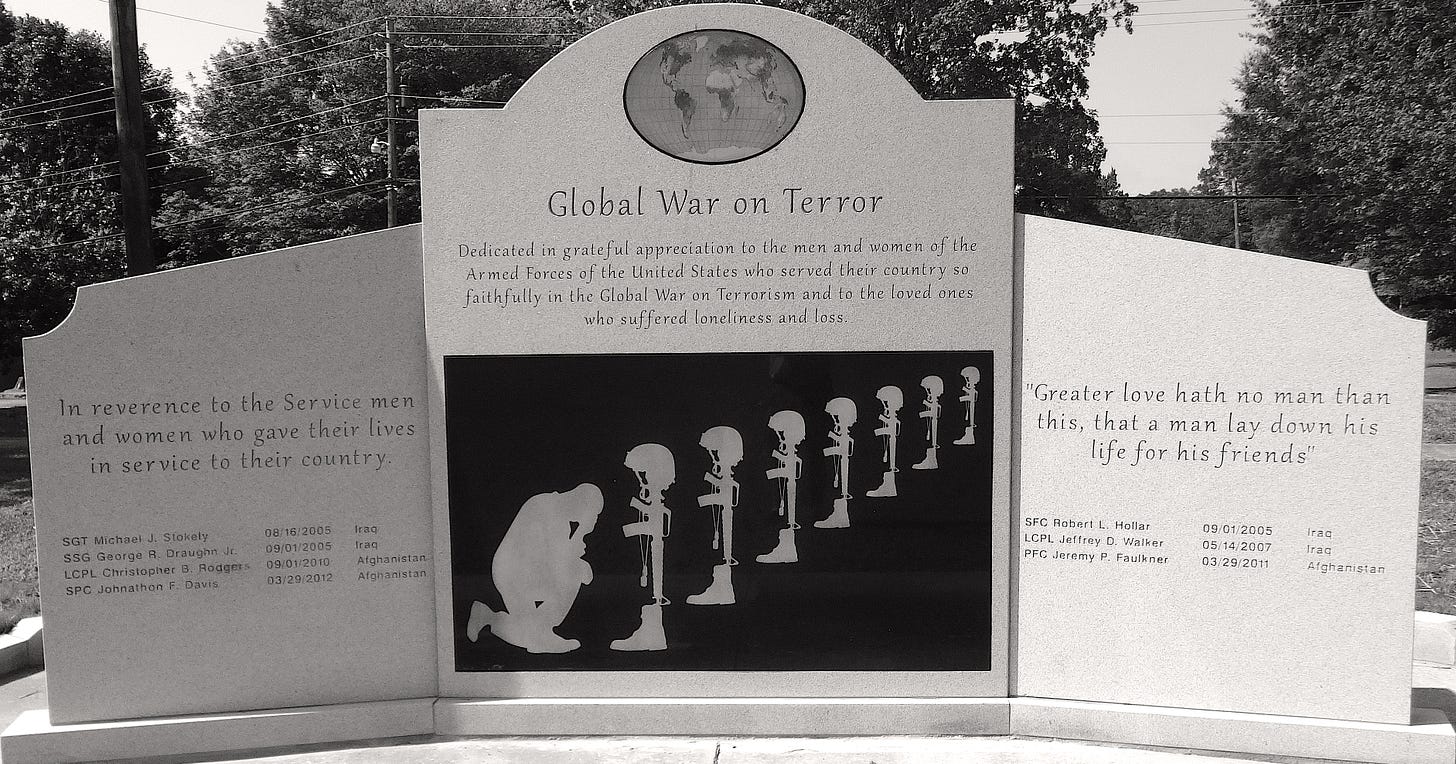

(Global War on Terror memorial, Griffin, Spalding County, Georgia. 2015. / Michael Rivera, via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0))

NEVERMIND THE LANGUAGE, WHAT ABOUT THE ROBOTS

The machines of war iterate in cycles, and with tanks now over a century old, robot tanks are starting to replicate some early armor designs. At Forbes, I wrote about Serbia’s Miloš robot tanklet, and how it resembles the Renault FT of World War I.

Also at Forbes, I returned to the Fixar drone, a weird tilt-body Russian robot, designed to both fit in a packable case and fly efficiently in more extreme weather than most drones.

For Breaking Defense, I wrote about the Defense Information Systems Agency awarding a contract worth almost $200 million for secure cloud browsing. It’s an attempt to reduce the amount of downloading that comes with normal internet browsing, and in so doing, quarantine threats to the rented servers, instead of actual military computers.

Back at Forbes, I took the announcement of Amazon Ring’s home security drone to talk about what kind of security people can actually get from a flying robot with a camera that stores video in someone else’s computer. Not a lot, but maybe worth it if the privacy tradeoff is fine compared to an enduring fear of having left a stove on.

I would be remiss, also, to not use this opportunity to talk about the writing going on at Fellow Travelers Blog. Polling shows that ending the Forever War is popular among people who vote for Democrats, and given the series of present crises, it seems very silly to not run on the very popular policy, even for candidates who once supported the wars in the past.

I very much enjoy writing like this, and reader support is what lets me take it from a weird, time-intensive hobby into part of my patched-together freelance income. Paid subscribers will gain access to more ways to directly contact me, and I’ve included a survey in my paid posts so I can better respond to what it is that subscribers actually want me to cover.

That’s all for this fortnight. Thank you all for reading, and if you’re in the mood for more newsletters, may I recommend checking out what we’re doing over at Discontents?

As a special bonus, this week’s Discontents starts with an introduction from me, talking about the car as a weapon.