Inert? Call Bert!

Lessons for managing expectations in a long emergency from the protagonist of Duck and Cover.

Edited by Althea May Atherton

When faced with the prospect of surviving an apocalypse, the United States of the early Cold War decided to teach children a song.

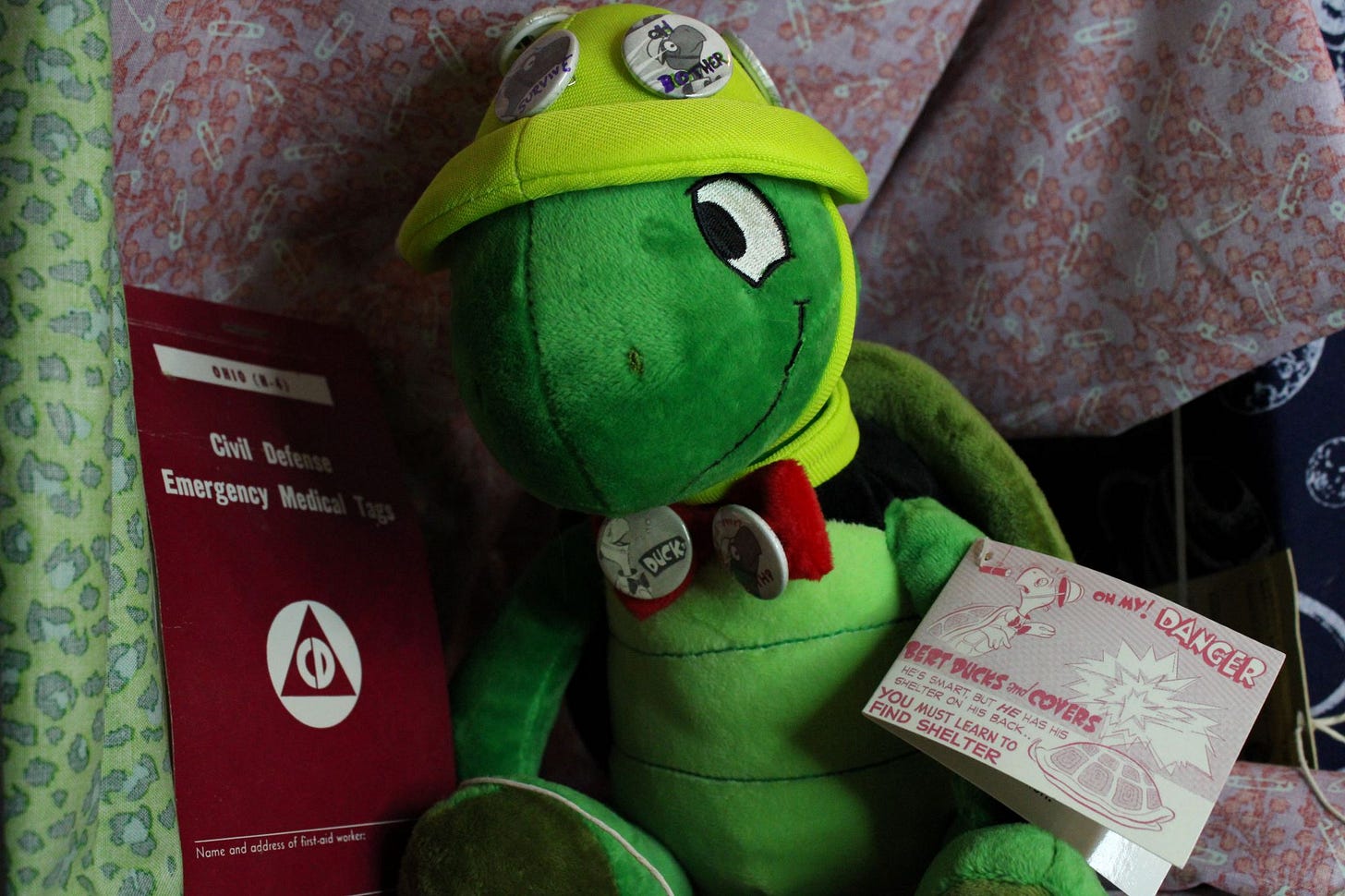

Sitting over my shoulder as I write this is a stuffed toy of Bert the Turtle. Bert is a mascot for perhaps the most mocked public safety campaign of the nuclear era. Bert is a gift from Marty Pfieffer, and the toy version comes with a donation to a sea turtle recovery effort. Bert the Turtle is is the mascot of "Duck and Cover"

Below is the full video. “Bert the Turtle” continues until about 1:20 and then again at 9 minutes:

I, like many people with a casual interest in enduring nuclear peril, had thought of Bert as a cruel joke, the 1950s equivalent of telling schoolchildren to throw pencils at an active shooter. Surely, the logic was to give the illusion of safety and control in the face of a staggering terror. Telling kids to fall and seek shelter in the moment between warning siren and blast felt, to my cynical mind, more about encouraging children to face oblivion in an orderly fashion, rather than actually changing their survival odds.

What changed my perspective was a conversation about Civil Defense with nuclear historian Alex Wellerstein. Established by President Truman in 1950, the Federal Civil Defense Administration was tasked with working through an extraordinarily grim problem: in the likely event of a nuclear war, what could the United States have done beforehand to ensure the survival of the most citizens, and let the country function as closely as possible to before?

There's a couple competing logics to Civil Defense. One is the complicated role of preparations for war in the logics of deterrence and compellence. If, say, the US could guarantee the survival of 70% of its population after a nuclear exchange, but the USSR could have only guaranteed the survival of 50%, then the US had somewhat less to lose in a crisis by escalating to oblivion. I don't find this line of thought compelling, but it was present and tells some of the story.

The other logic of Civil Defense is simply ensuring that enough people within the US survived to make government and life possible afterwards. It's under this mission that Bert the Turtle makes some sort of sense.

At the scale of a nation, Duck and Cover can mean more people live after a nuclear blast than otherwise would have. This is a survival that happens on the margins, in the outer bands of radius from the blast. It's here, where getting out of the line of a window can be life or death, that the likelihood of survival could be meaningfully changed through drills. On the scale of nuclear war, increasing survival for some by even modest percentages means a different outcome of millions of lives.

In order to get that marginal saving, Civil Defense needed everyone to learn the same drill, as though they were guaranteed to be in that meaningful radius. Duck and Cover is messaging about one action, designed to save some people, taught as a universal.

I was thinking about Bert and Duck and Cover the week after Christmas, when the CDC rolling out new guidance became a meme on incompetent communication. The new guidance for individuals who test positive was a change urged by the CEO of Delta Airlines, and it comes on the heels of a series of failures in messaging.

To that end, I rewrote the lyrics to Duck and Cover, imagining what it would be like if the CDC had the same message discipline as Civil Defense.

There was a turtle by the name of Bert

And Bert the Turtle was very alert

When disease threatened him he never got hurt

He knew just what to do

He'd test and stay put, test and stay put

He'd cover his mouth and nose and just be remote

He'd test and stay put!

For completeness sake:

He stayed inside his little home until the test was clear

Then one by one his cough and fatigue and spreading would all clear

By acting calm and cool he proved he was a hero, too

For finding safety is the bravest wisest thing to do

And now his little friends are just like Bert

And every turtle is very alert

When disease persists them they rarely get hurt

They know just what to do

They test and stay put, test and stay put

They cover their mouths and noses and just stay remoteThey test and stay put!

I can’t recall exactly what inspired the specific lyrics, but it seems based on the three general behavioral changes of pandemic life, designed to reduce the burden every individual places on the existing medical system. Masking when sick, common in other countries before the pandemic, moved to a default position, even as the boundaries of where and how to mask shifted. (In the process, early in the 2020 stage of the pandemic, people rediscovered the masking campaigns of the 1918 flu pandemics). Isolating and testing, too, became clear early actions to take in the face of the pandemic.

This was, at least for a brief stretch of time, a set of personal actions explicitly endorsed and supported by the federal government, as Congress passed stimulus checks and unemployment spending increases and a new child tax credit, plus bucket of cash to businesses on the premise that they would be ready to rehire workers once this was all over.

There’s plenty to be written about what changed between the Spring 2020 response and the Winter 2021-2022 response. What’s most crucial for capturing this moment is that while elected leaders may treat them as distinct events, they are instead one continuous crisis, felt especially by workers in healthcare.

A few days before the CDC published its shortened isolation guidelines, the science reporting team at The Atlantic published “Omicron Is Our Past Pandemic Mistakes on Fast-Forward.” It’s a good look at what makes a sustained pandemic so much harder than an outbreak. The US, which was never abundant with healthcare access, is continuing to experience healthcare scarcity. The price barrier to accessing care persists, even with the relatively low-cost items like tests and effective masks. The new scarcity is that the people, trained and authorized to provide that care, are worn, depleted, and leaving the field.

This is, like much of the dying in the pandemic, a largely invisible change to everyone not immediately in a hospital. It’s belied by the refusal to see the Christmas holiday as a moment of gathering and spread. Largely, the state and local governments who are implementing new restrictions chose to do so after the holiday, when it’s politically convenient, instead of before, when it’s unflattering news.

Duck and Cover works as a civil defense drill, to the extent that any part of Civil Defense worked, because it’s an action that can be reduced to muscle memory, and one where the success of it is revealed in the space of minutes. No one is expected to accomplish any work in the minutes between hearing the air raid siren and knowing if they have, in fact, survived a nuclear attack. If the sirens were a false alarm, they could soon return to their normal work, and if it was not, they could begin the work of rebuilding their community.

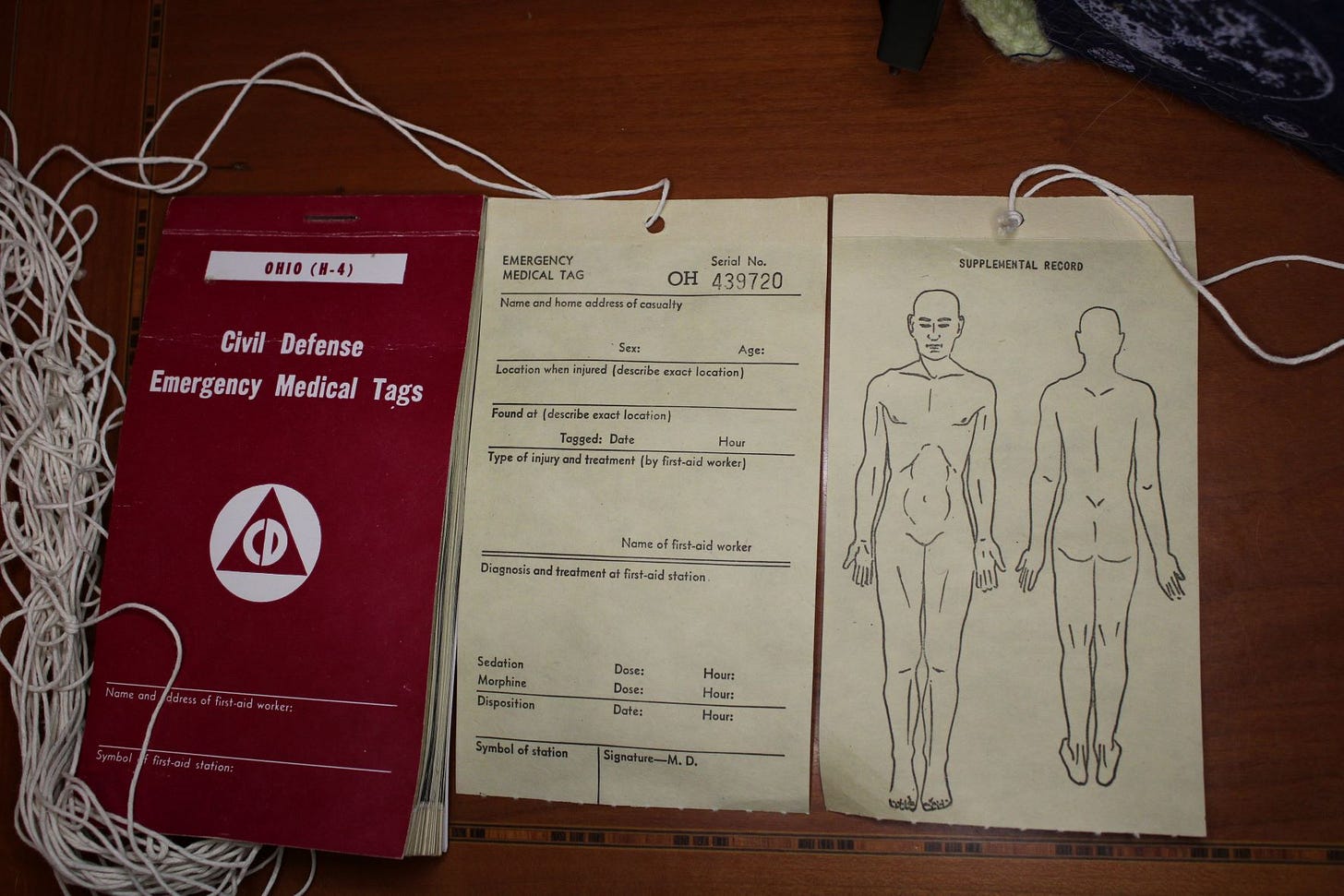

Post-nuclear fiction, and much of the popular imagination, tends to see the nuclear war as an epochal event, one that by definition creates both a before-time and an after-time. Civil Defense drills and plannings were all designed to carry as much of what existed in the before-time into the after-time, where it could be rebuilt. The waves of danger during a nuclear attack are separated by hours or at most days, not months. Once inside a fallout shelter, people were expected to pass the time surviving, not phoning into meetings or preparing presentations on sales figures. During the actual emergency of a nuclear war, civilian service to the economy was put on hold. (Civil Defense did demonstrate that the paperwork tracking debts could survive a blast in a filing cabinet, even if the specific human debt collectors died in the process).

Wellerstein’s shared pamphlets for executives on what to do “If An A-Bomb Falls” and “Mortuary Services in Civil Defense.” The latter is particularly visceral: “The individual care we traditionally bestow on our deceased will not be physically possible when the dead must be counted in the thousands. However, [Federal Civil Defense Administration], with the assistance of its Religious Advisory Committee, is planning for suitable memorial services for the dead in areas devastated by enemy attack.”

That’s a horrific prospect, and also a guaranteed inevitability from any use of nuclear weapons.

Wellerstein describes this prospect as hyperreal, “more real in its clinical matter-of-factness than farce could ever be.” By the nature of its timing and mechanism, nuclear wars do almost all their killing at once. It’s a temporally laden moment, akin to a storm or an earthquake or any other rapid natural disaster, but at almost incomprehensible scale.

As I’m writing this, on January 12, 2022, total deaths from COVID in the US have exceeded 843,000. That is, in absolute terms, more than twice as many people as died in the US from World War II. It is 7.6 times the low-end estimate for how many people the US killed with atom bombs over Hiroshima and Nagasaki; at the high-end estimate, COVID in the US has killed 4 times as many people.

Between revisions and publication, it’s likely that number creeps up by 9,000 or so.

If the pandemic deaths had happened all at once, if they had been bound together temporally in the way that deaths from nuclear war would be, the loss would feel abrupt. There would be a clear after as well as a distinct before-time. We do not have that. Pandemics operate on different logic and by a different mechanism. While there is no clear after, yet, people have adjusted expectations to the long now of the crisis, with all approximations of pre-pandemic normal coming in the dips between waves.

It’s impossible to say how well Civil Defense would have worked in the aftermath of a nuclear war. Perhaps the drills would have saved a meaningful margin of people. Perhaps the undertakers and local government officials, equipped with authoritative government-produced pamphlets, would have set about digging trenches for irradiated corpses, rituals of mourning adjusted en masse in response.

When the danger had cleared, people might not have gone back to their old jobs, but they could have together found ways to survive and be useful to one another, as people always have following crises. With a sharp before, a violent delineation, and a new normal set entirely in the after, and presumably with the world’s arsenals expended in the at-most weeks-long conflagration, people could build that new life together. Civil Defense, if it established any institutional capacity and was not seen as immediately tainted for its role in the before-time, might have played some part in this reconstruction.

At present, against the very first signs of the omicron wave possibly receding, it is clear that the organs of government set to manage a long emergency have failed. More than that, given how much time has passed, the government has failed to build new capacity for emergency. Something as straightforward as the federal government supplying Covid tests to schools is only happening in Spring 2022, despite the administration debating whether or not to distribute masks and tests back in October 2021.

Bert the Turtle is an absurd avatar. It is a minor accommodation to a grim reality, a simple answer of what to do that avoids the harder task of trying to ensure we see a tomorrow with no nuclear weapons. Yet despite all that, I can’t help but imagine what 2022 would look like if the federal government applied any of the same driving vision to our current crisis, that not only was it survivable but that proactive action, federally directed, could safely shepherd people through a long emergency and usher about a safe future.

Thank you all for reading this. Having this work and this place sustains me as a writer, especially when I’m working on drier stories. To that end, I encourage everyone to read “How Silicon Valley Is Helping the Pentagon Automate Finding Targets,” a deep dive I’ve been working on since October. It’s about automating video analysis, and it’s about how the US is leaning on tech to fight wars authorized long ago.

Over at Discontents, my colleagues have written incredible work about massive failures of governance and media. After the Washington Post and other outlets framed the story around an experimental organ transplant around the recipients criminal record, Libby Watson of Sick Note returned to look at the broader systemic failings in organ allocation that don’t get massive coverage.

It’s an important story, and one I’m happy to see Discontents cover.

I remember in the dawn of the pandemic when someone asked me why everyone was buying all the damn toilet paper. Pretty sure it was a rhetorical question, but I did have an answer.

It's because a generalized disaster response script we've been training people to follow for decades was followed...for the wrong disaster. Earthquake, blizzard, hurricane, tornado, and wildfire all have the same script immediately before or after event: get clean water, canned food, toilet paper and fill your gas tank. When told there was A Crisis, people went to default crisis prep model. It's kinda pleasing, if wrong in the circumstances.