Edited by Althea May Atherton

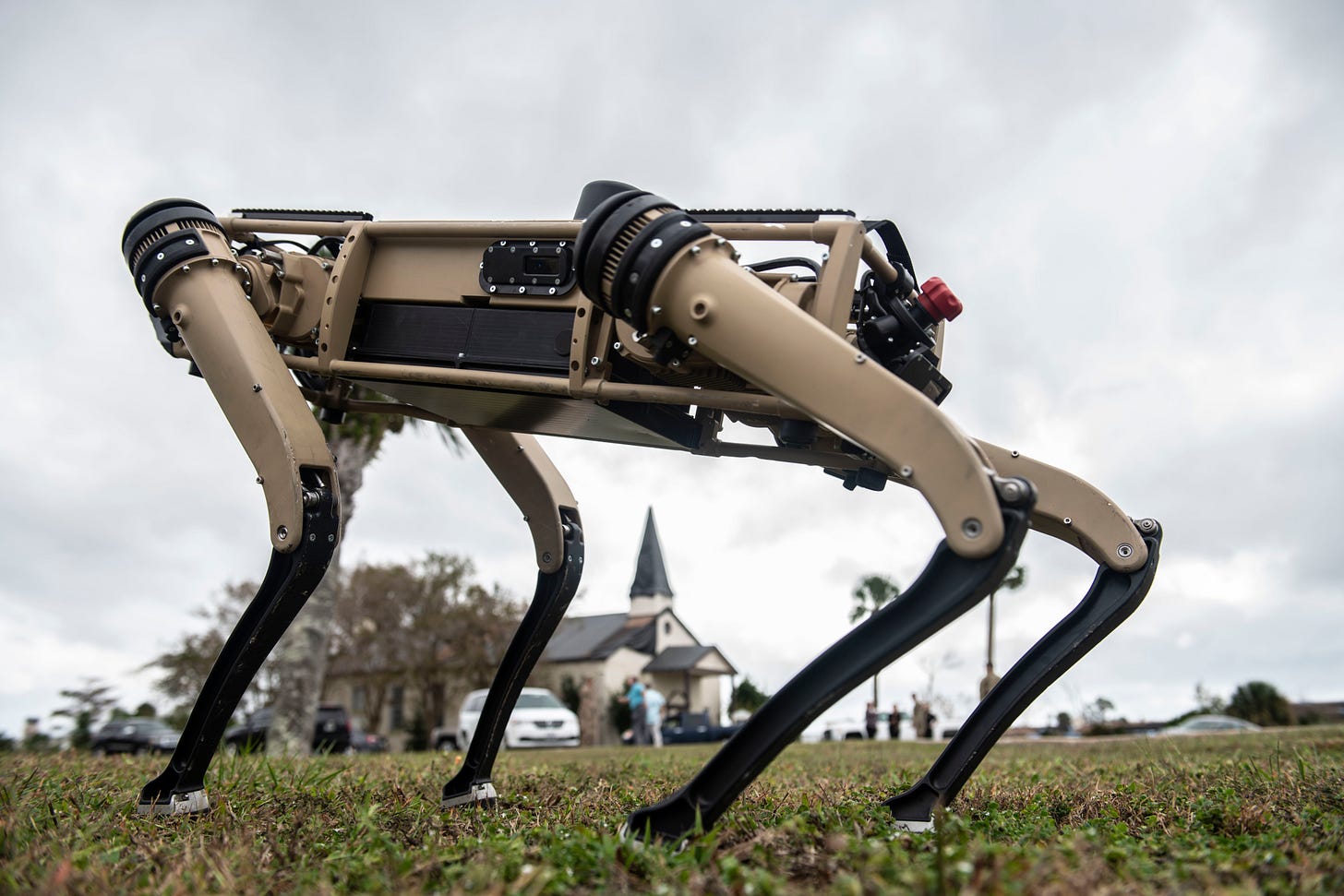

A month before the Quadrupedal Uncrewed Ground Vehicle (Q-UGV) by Ghost Robotics rocketed into public consciousness with a gun on its back, it could be seen on YouTube trotting through the swamp at Tyndall Air Force Base. In that video, which has a respectable 66,000 views at the time of this writing, the robot splashed through the water, surfaces before a ramp, and then appears to read a QR code as it loads itself into a recharging station in a shipping crate. A more enchanted writer, enamored by the machine imitating an animal, might see this as nestling into a den for a nap. To my eye, it’s roughly as cozy as parking a lawn mower in a garage.

The Q-UGV, not to be confused with Boston Dynamics’ famed BigDog, is neither the first dog-shaped robot, nor is it the first robot to carry a gun. Instead, it is one of, if not the first machine, to combine both traits and in so doing, it became the cleanest foreshadowing of robot war.

As astute Discontents readers will remember, I promised a story about Robot Dogs of War back in October, with an eye towards answering the robot weaponeer’s perpetual question: why does this machine feel more unsettling than any other form of mechanized murder?

I was one of a barrage of journalists who all wrote stories about the debut of the Special Purpose Unmanned Rifle (SPUR), mounted on the back of Ghost’s Q-UGV. This gun, built by a company that makes rifles for special forces, is billed as offering “precision fire from unmanned platforms” thanks to its “highly capable sensors,” traits that imply an autonomous weapon.

The SPUR-equipped Q-UGV (technically a Vision-60 model, but to all the world a “robot dog”) was on display at the Association of the United States Army (AUSA) conference. AUSA is technically a private group, organized around advocating for the army, making the AUSA conference a weird mix of arms exposition and industry workshopping. It is a lynch-pin of the entire defense trade press calendar.

I attended AUSA in person a few times before the pandemic. With tanks rolled inside display halls inside DC’s Walter E. Washington Convention Center, the conference is one of the most straightforward showcases of the business of war.

In the immediate aftermath of media coverage of the gun on the robot dog, Ghost Robotics' CEO Jiren Parikh spoke to IEEE Spectrum’s Evan Ackerman. In the interview, he clarifies the limits of the robot dog’s autonomy with details that might have been clearer on the showroom floor. He also places its autonomy in context to other weapons.

“Decades ago, we had guided missiles, which are basically robots with weapons on them. People don't consider it a robot, but that's what it is,” said Parikh. “More recently, there have been drones and ground robots with weapons on them. But they didn't have legs, and they're not invoking this evolutionary memory of predators.”

Parikh goes on to invoke science fiction and social media in the next line, but I think there’s something more telling in this notion of “evolutionary memory of predators.”

Here’s the video of the Q-UGV walking around Tyndall Air Force Base:

In motion, the robot feels animal. I know how limbs and joints move. I can hear it in the water, see it in the grasses around the robot’s feet. When it stands in the mush on the edge of gravel before the ramp, I get a sense memory of the shallows at a swimming hole in the Jemez Mountains. No tracked robot has ever invoked the sensation of sinking my toes into mud and algae. In motion, if you can overlook the desert-beige casing, it does a pretty good impression of alive. At least, until it pauses to read a QR code and then park with its back exposed to an open doorway.

What this does not invoke, in any sense of the word, is a predator.

The Vision-60 Q-UGV circled the internet as a robot dog because its behavior (and that of other legged robots) invokes companion animals, not hunters. It is also, in no small part, called “robot dog” or misidentified as BigDog or Spot because Vision-60 Q-UGV is a sterile name for what is a far more evocative machine.

Ghost Robotics has worked in this field for a while. I first covered a Ghost-made machine called the Minitaur in 2016, and again with some more depth in 2017. Minitaur is tiny. In the first story, it jumps. (There was, briefly, a time where a whole internet story could be a gif of a robot jumping). In the second, Minitaur stumbles over rocks, crawls under a car, and scampers over ice.

In my notes from an interview with the Ghost Robotics co-founders and Parikh, dated March 2017, Parikh mentions the Army Research Lab testing the Minitaurs. Parikh saw a military market for the robots, saying, “we’re not building these robots as warfare devices, but there’s so many applications, especially ISR, intelligence, reconnaissance, surveillance.”

There are a host of reasons the Minitaur would make a bad weapon, most especially that it is too small to meaningfully hold a weapon. Sensors, like cameras or microphones, can easily ride on a small robot.

Both the Minitaur and the much-larger Vision-60 exist as platforms first, working bodies that can carry payloads as needed. “Payload” serves as a sterile catch-all for everything from sensors to radios to weapons, the plug-and-play parts on a modern war machine. What makes the platforms work smoothly are sensors placed on the robot’s leg actuators, which could interpret current fluctuation the way a body sees muscle tension and send signals rebalance accordingly. It looks, in both forms, lifelike.

The earliest mention I could find of any robot dog in Popular Science comes from the May 1930 issue. “Robot Watchdog Fights When Light Hits It” is a report from a radio show exhibition in Paris. The machine is light-triggered, with a flash of light sending the robot rolling forward, snapping open and shut its jaws, and triggering a “phonographic reproduction of a ferocious bark.” The robot dog comes with a major caveat: it only works if it is “confronted by a burglar carrying a flashlight,” though the makers promised follow-up on audio triggers. (I found no further reports of the device.)

For the better part of a century, every other robot dog I could find in the PopSci archives was a piece of entertainment or a teaching tool. This includes Elektro and Sparko from 1949, the Computerized Personal Robots of 1983, Aibo in 1999, and Papero in 2005. All of these draw on dogs as companions, of robots borrowing that form for comfort. Very, very few of them use legs in any meaningful way for anything beyond expression.

This streak ended in January 2006, with “Robots Go To War,” a splashy 9-page cover story, which features the earliest mention I could find of Boston Dynamics.

“Boston Dynamics is working on a variety of biologically inspired robots. Two of its four-legged ‘bots -- BigDog and LittleDog -- could become a soldier’s best friends,” wrote Preston Lerner. The concept was for a gas-powered legged machine that could sense terrain, routing around or over difficult obstacles.

BigDog makes a second PopSci appearance April 2006, in “The Army’s Robot Sherpa.” This story is explicitly on BigDog’s origins as a DARPA-funded project, military utility its whole reason for being. The purpose given is, “to haul soldiers’ gear into battle--through terrain no other vehicle could negotiate.”

This was the state of BigDog when I started writing about it in 2013. The robot, a long-in-the-works DAPRA-funded project to build a military mule, could balance and stumble over terrain. Its selling point was carrying up to 400 pounds of gear, lightening the loads of gear-laden soldiers in modern combat.

The Legged Support System (LS3) was a big BigDog variant that the Marine Corps experimented with in exercises in 2014, matching the 8-year promise from 2006 for BigDog to participate in exercises. Ultimately, the LS3 was rejected from use because the same gas-powered motor that made it useful for carrying gear was too loud to operate in rough terrain. Better carry everything with people than risk a rumbling robot giving away a concealed position.

In 2015, marines trained with a Boston Dynamics Spot robot, in an early form that feels almost alien to its sleek, plastic-bodied modern appearance. For this exercise the robot was a scout, going into rooms before the marines followed to clear them. Boston Dynamics now shared videos of Spot doing dances and also accompanying police on duty.

There are other robots in this category (on acronym alone I’m inclined towards the LLAMA, or Legged Locomotion and Movement Adaptation), but we’re finally at the point where the dog-shaped robots are no longer experiments or concepts. They are real, working machines, sold and tested by governments and militaries. In terms of tech alone, it’s impressive that multiple companies have figured out distinct ways to make legged machines work. (Concurrent revolutions in battery power, small sensors, and processing power certainly helped.)

That means the question for the machine makers, and broadly the public and policymakers too, is no longer “can it work?” but, “what will it mean when it does?”

“We will get used to these robots just like armed drones, they just have to be socialized,” Parikh told IEEE Spectrum in that same interview. “If our robot had tracks on it instead of legs, nobody would be paying attention. We just have to get used to robots with legs.”

Let’s for a moment accept Parikh’s premise that this is about legs instead of tracks. It is, I think, a meaningful difference. Legged robots, especially effective ones, can follow people up stairs and over rough terrain. A robot stumbling and recovering on ice with all the grace of a newborn deer reads as alive enough to continue a pursuit. There are tracked robots with extensions that can climb stairs, but there is still something distinct about a robot following people inside that evokes a special fear.

When I write about the future of war robots, and the present of war robots, I like to include the tracked machines alongside the flying machines and the walking machines. Given the choice of a robot to anchor my New York Times piece, I picked Estonia’s THeMIS (Tracked Hybrid Modular Infantry System), a robot that is a platform for weapons between two big tracks. This is largely the shape of robots already in use, in line to be adopted by militaries, and likely to be used by commanders in combat at some point.

I can’t make people pay attention to a robot that looks like a small tank more than people are inclined to follow a robot that moves like a beloved pet. I also don’t really need to, because the different machines force the same questions: what parts of this are autonomy, what parts are controlled or directed by humans, and under what circumstances will people use the weapon on this robot to kill other people?

These questions are relevant even when the machine is just a scout, or just a mule, or just a courier. Even without the Trump-era rebranding of all military functions as in service of lethality, every military function ultimately supports the same end goal. Scouted positions, mule-hauled ammunition, or robot-delivered hand-written orders all work towards directed violence.

Putting the gun on the robot dog makes the intent impossible to hide. This is a robot that will be used by people to do harm to other people. The ad copy for the rifle would not mention the kinds of bullets used or the precision of the weapon if this was all an academic debate.

For the first decade of BigDog, the question was if the machine would work at all. Now, with a host of legged robots demonstrably following human commands and in tests by militaries and police forces, what matters most is the degree of human control and machine autonomy.

Autonomy and human control are both technical and policy questions, and it’s easy to lose sight of one or the other part when writing about a new machine. This was true for drones and drone strikes when I first started in journalism. To the extent that people are now socialized to armed drones, they understand the machine as a weapon and the choices in who the weapon is used to kill as a policy decision.

If anything, a socialization on robot dogs will further cement the machines as permanent occupants of the uncanny valley of death. There are many ways to think about robot dogs, but only one is possible when staring down the barrel of a machine-wielded gun.

Thank you all for reading this. As I’ve promised in Discontents, I have an upcoming newsletter on The NDAA As Industrial Policy in the works, and a host of other ideas to cover, too. I also took the time to write about Dune and Empire, which was a fun little jaunt.

In addition, may I recommend checking out what everyone else is doing over at Discontents? Recently I’ve enjoyed this entry from Max Read of Read Max, about the entire internet as built of durable scams, which cannot be fixed by more scams.