Fear Squads And Tread Naught

Armor and not-quite-armor in modern warfare

Edited by Althea May Atherton.

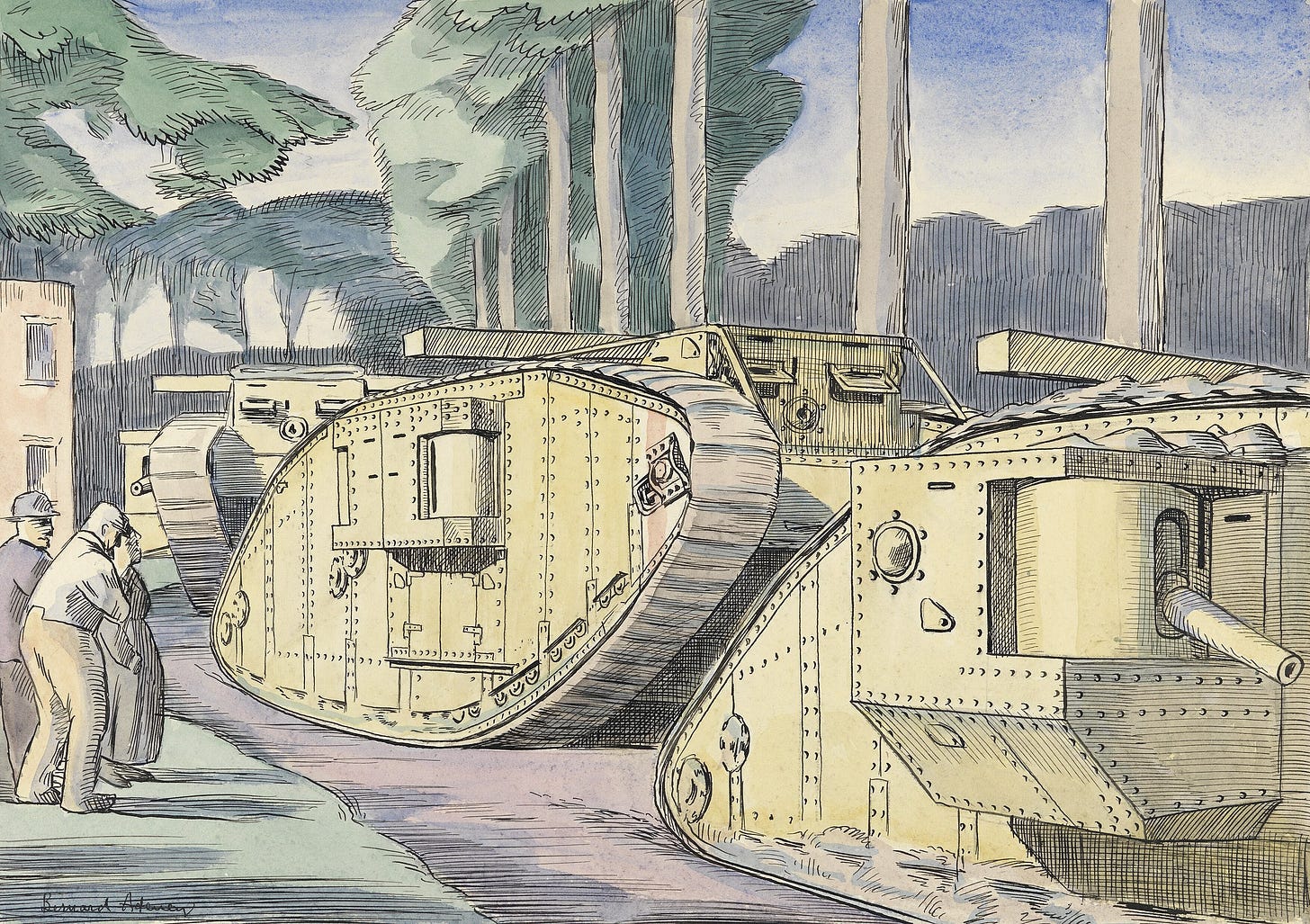

When treaded armored vehicles first rolled into battle in 1916, they were categorized not by weight or role, but by gender. The Royal Army, seeking to break the stalemate on the Western Front, devised these “dreadnoughts of the battlefield,” and then made two versions. If the land battleships were armed primarily with machine guns, they were female, while if they had two 57mm cannons, they were male.

Regardless of the assigned gender of the tank, their role in battle was the same: break through enemy lines, allowing soldiers and unarmored vehicles to follow through and exploit the gap. While tanks and planes would emerge as among the most iconic technological innovations of The Great War, it’s the machines of defense that truly set the shape of warfare.

The tech going into the war was a staggering array of defensive tools, none more powerful than the heavy machine gun.

What is truly remarkable (and what I had not learned until 2022) is that the British government fully underestimated the power of machine guns to turn fluid battle lines into fixed killing fields. At the Critical State newsletter, I summarized Marija Grinberg’s paper “Wartime Commercial Policy and Trade between Enemies.” Grinberg details how sanctions evolve over the course of war, often ending at a goal of total economic isolation but starting at a position of minimizing hurdles to post-war restart of normal trade.

“Interestingly, machine guns were not prohibited from trade [with Germany] at the beginning of the war, as there was a wide consensus that they were useful only in wars of attrition, not in maneuver warfare,” writes Grinberg. “Thus, carriages and mountings for machine guns were forbidden from export at the start of the war, but not machine guns themselves.”

Prior to a February 1915 policy change, even after the first battles of Marne and Ypres, British gunmakers were free to sell their wares to Germany. What the machine guns did in conjunction with artillery and the massive armies that crowded battlefields was turn assaults into massacres. Defense has so long held an advantage in war that its power is a Clausewitzian maxim, the Prussian war theorist asserting that armies can both be too weak to assault while being undeniably favored in defense.

This is the war that birthed tanks, and it’s the circumstance in war in which tanks continue to be deeply, profoundly relevant.

Tank U, Next

As Russia's 2022 invasion of Ukraine entered its eleventh month and President Zelensky addressed the US Congress in December 2022, focus in the American defense press narrowed to the specific tanks Ukraine requested. I am, by geography and disposition, far from the leaks on what sort of developments will happen in the supply of premium military equipment, and so assumed I would be free to write a meditation on tanks here, and file stories about other vehicles at my contributor positions.

“M1 Abrams tanks and other armored vehicles could change how Ukraine fights,” written for Popular Science, did not start as a story about tanks, though the role of heavy armor in the battlefield was always part of it. Instead, the draft focused on Strykers, the eight-wheeled armored vehicles that exist at a medium level between lighter transports and tank-heavy formations.

I pitched it as a placeholder to talk about armor as a concept, and to highlight a family of vehicles that are part of the overall picture, if less flashy than the heavy armor of an M1 Abrams. And then, the morning the story went into edits, reports came in that the White House was considering sending Ukraine Abrams tanks, that Germany was going to send its own Leopard tanks, and most importantly, that Germany was going to lift its hold on other countries sending their own Leopard tanks to Ukraine.

So, my editor and I wrote that into the draft, moved the news to the headline, and I punted on finishing this for a few more days. The semantic debate over what was and wasn’t a tank, nudged by France’s decision to send the armored, wheeled, and heavy gun equipped AMX-10 RC, occupied a month.

For people who spend too much time online arguing about what is and isn’t a tank, it was a pretty good month.

Ukraine’s Ministry of Defense addressed it satirically, with an English-language video styled after a truck ad. An M1A2 Abrams (the most modern version of the US’s tank), wasn’t a tank, it was simply a “Recreational Utility Vehicle.”

The decisions this week by NATO members to send Ukraine Leopards, Abrams, and Challengers (the UK’s contribution of main battle tanks) basically obliterated the goofy discourse. Everyone broadly agrees that if tank means anything, it means these three vehicles, and they can join the Soviet- and Russian-pattern models already in service in Ukraine’s military.

Armor for what, and to what end?

In my story about Strykers that turned into a story about Abrams, I settled on a rough dichotomy for tankiness. “Armor,” the broader category for vehicles moving faster than humans and protected against weapons, is full of gradations, but the most important distinction is the end to which that armor is used. In this, I settled on “armor for moving” and “armor for fighting” as the broadest categories.

Part of what I like about writing for Popular Science and general interest (as opposed to trade) publications is getting to dive into the foundational assumptions of what makes a machine work. It’s why I went back to the origins of tanks for this piece, examining the distinctions made at the time.

The first tanks existed to break through enemy trenches, and to provide protection for soldiers traveling behind them. The tanks were not themselves transports, but they were essential for figuring out how an army could advance. The machine guns on ‘female’ tanks and the cannons on ‘male’ tanks served the same ends, killing defenders and pinning others in place. Armor is vital to that end, because it allowed the tanks to advance and become threats, requiring specialized weapons to defeat and disable.

This has now become my functional definition: A tank is any vehicle that can be expected to break a defended position, allowing advance.

Abrams, Leopards, Challengers, the T-series tanks used by both Russia and Ukraine, all obviously fit this bill. Heavy cannons can destroy bodies, vehicles, and weapon emplacements alike. Machine guns can pin down defenders. The heavy armor and advancing speed of treads over rough terrain requires dedicated defenses, even if those defenses are almost a century old in design.

What I like about this definition, though, is that it is not limited to only describing Main Battle Tanks as a category. Tanks and tankiness, here, becomes relative to the defender. Against a line held by hardened troops, complete with anti-tank missile launchers, tank traps, artillery, and air support, then a main battle tank is about the only vehicle that can meet the definition.

Even land wars in Eurasia, complete with set-piece arrangements of forces and weapons, don’t always line up to that same hard standard.

The Bradley Infantry Fighting Vehicle, which sits between the Stryker and Abrams in terms of armor and armament, is a good example. The Bradley is a transport, though with just over half the capacity of a Stryker. It has a main cannon mounted on a turret, though at 25mm it shoots much smaller ammunition than the 120mm rounds of an Abrams. It has heavier armor, but not the heaviest armor.

Against tanks, the Bradley is capable (if armed with anti-tank missiles) but it’s not designed to fight that battle, and its crew will likely need to flee to safety, wait for heavier support, or pick a different place to attack. But against a position defended by rifles, machine guns, and rocket-propelled grenades, a Bradley is more than capable of charging into the defenses, killing or routing the defenders, and spearheading a breakthrough.

This process scales all the way down to police vehicles on streets outside of war. A police armored car, like a military surplus MRAP or a built-for-SWAT vehicle like a Bearcat, can function as tanks, especially against protestors armed with little more than slogans and determination. Mounted police, modern descendants of cavalry soldiers, can and have been used to break crowds of protestors in much the same way as vehicles.

Armor is, largely, what armor does.

Thank you for reading! I am, as ever, delighted to get to write for you, fleshing out an idea that doesn’t have an easy home elsewhere. This story pulled me through a wealth of archival material, some of which you can find on Twitter, and which I hope to turn into another post in its own right.

![This Baby Caterpillar Tank Looks Dangerous But Isn't The miniature caterpillar tanks shown in the accompanying illustration is not an instrument of war, nor is it intended to become one. It was made at the request of the Red Cross Organization of Stockton, California, by a local manufacturer of caterpillar tractors, to be used as an attraction in a society circus, which netted nearly $10,000. The exterior of the tank was patterned after the English tanks used on the battlefield. A motorcycle engine was put in to supply the power for the motion of the track chains. It was so arranged that wither side could be disconnected or work independently, thus permitting sharp turns. A one-man tank built like one of the big English tanks, but intended for a less bellicose purpose. [Illustration shows a person-sized tank with a driver standing in the back] This Baby Caterpillar Tank Looks Dangerous But Isn't The miniature caterpillar tanks shown in the accompanying illustration is not an instrument of war, nor is it intended to become one. It was made at the request of the Red Cross Organization of Stockton, California, by a local manufacturer of caterpillar tractors, to be used as an attraction in a society circus, which netted nearly $10,000. The exterior of the tank was patterned after the English tanks used on the battlefield. A motorcycle engine was put in to supply the power for the motion of the track chains. It was so arranged that wither side could be disconnected or work independently, thus permitting sharp turns. A one-man tank built like one of the big English tanks, but intended for a less bellicose purpose. [Illustration shows a person-sized tank with a driver standing in the back]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!MF1A!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fe23c319d-75eb-449b-86b3-86b19901f6b7_454x339.png)

If you’re new, welcome! If you’re returning, I’ve restarted payments to support my work here. No hard feelings if supporting this letter is no longer in your budget or interests. If you do stick around or haven’t subscribed before and have a few dollars to spare in your budget, know that I really appreciate the support I get from readers directly. Thank you, and I look forward to writing for you more in the future.

I like the terse tank definition a lot! Except I think "A tank is any *land* vehicle ...". Otherwise aircraft and marine craft become tanks, I don't think that's what you meant. But the identification by role in the offense/defense model is spot on, and compatible/negotiable with other definitions derived that way. Thanks!