Reapers come in coffins. The iconic, era-defining drone gets shipped to its locations in a very large, expensive box, and the humans who handle the Reapers and their ilk call the large boxes coffins. The violence comes once the box is opened, once the contents are put to use.

There is a humanizing comfort in such a term, as though the remotely controlled robot is at rest until necromanced back into being by humans. It’s a tidy way to think: once the danger is in the coffin, it is managed.

I don’t have a drone story for you this week, but instead I can offer this: a look at two of the worst boxes people have ever sought safety in.

Consider, if you will, the Riot Shed.

As ably documented in the thread above, the Riot Shed is a metal box designed to, for an exorbitant price, protect its occupants from the scariest thing they read on the internet this week. Specifically, in the case of the flier shared above, that fear is death at the hands of antifascists. Set aside that the fear of violence from antifa is a kind of telling on yourself; what is really incredible about Riot Shed is how it lets fear of street scuffles turn into the marketing pitch for a shitty panic room.

It is a product that lends itself to grift: in order for someone to be interested in the product, they must already be somewhat detached from reality, and have a strangely skewed sense of what dangers exist in daily life. Overcome by fear of murderous violence at the hands of roving bands of, like, off-work bouncers and bicycle messengers, the ideal Riot Shed customer sees the flier, immediately makes the call, and never looks for a second provider beyond the brochure.

I cannot speak to the efficacy of a Riot Shed against bullets, though let me say that folks on twitter seem pretty skeptical. That the shed has only one door, with hinges on the outside, doesn’t seem particularly confidence-inspiring. There’s a full menu of upgrades for features, so a backyard death-trap can have benches or a deluxe gun rack, all of which will definitely matter in a real invasion of the suburbs by people whose default kind of violence is “making sure nazis doesn’t feel comfortable drinking at their local bar.”

But here’s what makes the grift perfect: if the Riot Shed fails to provide safety in a riot, who will be left alive to sue the Riot Shed makers?

It’s a product built to never be used, so it doesn’t matter that it is flawed from the foundation to the roof. As long as the check clears and the buyer feels safer, it might as well be an invisible suit of armor. The Emperor’s New Kevlar.

More than anything else, the grift of the Riot Shed reminds me of fallout shelters.

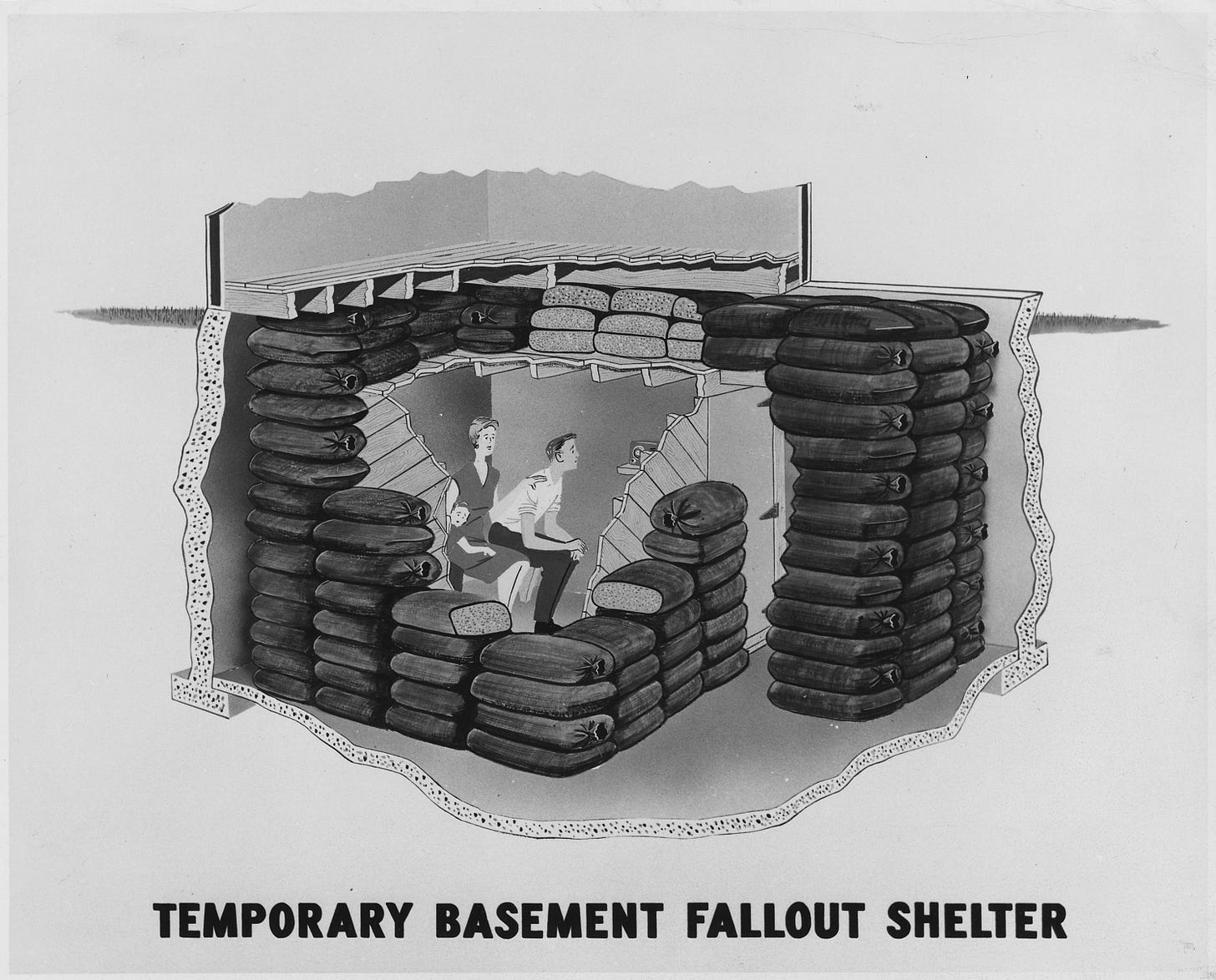

Fallout shelters are the early Cold War culmination of a real and useful kind of building: a bomb shelter. The photos of people enduring the blitz in the UK by hiding out in the underground stations are understandably iconic. Soil itself is especially good at absorbing the kinetic force of a blast, and deep enough underground, structures should be safe from some level of bombardment above.

Missiles and thermonuclear bombs so dominate our understanding of nuclear weapons that it’s easy to forget how, for the first decade of nuclear parity, Enola Gay-style bombings were the ceiling, not the floor, for how people understood nukes. Long-duration bomb shelters, in the imagination of early Cold War planners, made sense as a way to sustain people underground until the worst of the radiation had dissipated.

Civil Defense, the organization tasked with seeing if society itself could survive a nuclear war, took communal fallout shelters so seriously they recommended designating most of a shelter as a nonsmoking era. There was, at least for about a decade there, real planning for getting people into shelters together and having some portion of the population wait out the worst of the radiation. (Missiles and, more especially, thermonuclear bombs blasted that concept to oblivion).

That kind of misguided but communal-minded shelter is fascinating, but it’s less of a knowing grift than a bad plan.

What really sets the fallout shelter up as a proto-Riot Shed style scam is marketing it at the, well, nuclear family. Suburbia is an illusion of tranquility built on constant fear, and what fear could be more, er, atomized than the possibility that the Big One would come and you’d have to rush to secure your immediate family and no one else in the special shelter in your backyard, or your basement.

The great Twilight Zone episode “The Shelter” aired in 1961, right at the cresting peak of the major fallout shelter boom. In it, a family of three hides in their shelter. Outside, their neighbors, in the panic of the brief window between learning about an apocalypse and experiencing it first-hand, beg to be let in. Ultimately, Civil Defense announces it was a false alarm, but not before those unsheltered neighbors have banded together to build a battering ram and threaten the fortunate three inside the shelter.

For people selling shelters, the harrowing quandary of “will I have to shoot my neighbors to protect my underground bunker?” is never part of the marketing. The shelter sells on imagined safety, not realism.

That marketing included traveling dioramas and gimmicks. The most famous gimmick is the “fallout shelter honeymoon” of Melvin and Maria Mininson, who won a contest to spend two weeks together in a 12-ft. deep, 6 x 14ft. wide shelter, and stayed happily married for decades afterwards. (The shelter was so hastily built that the concrete had not yet set and cooled, which only, er, cements how much the backyard fallout shelter enterprise was built on never actually delivering a working product.)

The prospect of a backyard or basement bunker, designed for the worst few weeks of human life, lost appeal as weapons got better, and as the grift started to fall apart. There’s a great little story, published in the Albuquerque Journal in August 1961, about a fight between a maker of shelters and a reseller about, among other things, the sold shelters being flammable. Oops!

While the high-profile suburban grift of a fallout shelter seller has mostly faded, modern models exist, at high enough prices and with weird complex names. The market has squarely moved from the well-off suburbanites to people who own several homes, at least one of which is large enough to be called a ‘compound.’” (That “Fallout Shelter” these days most immediately links to a little video game of post-nuke survival doesn’t really help the grift.)

In its place, we have Riot Sheds, a new scam aimed at suburbanites seeking a bubble of protection from a scary world. There are reasons to want a kind of shelter; while fallout or mob assaults are exceptionally unlikely, having a storm-cellar style hiding place in wildfire country (increasingly, most of the arboreal west) is not the worst idea in the world.

But buying a Riot Shed means accepting the premise of the grift entirely. This is not a world of evaluating likely risks, weighing survival strategies, and picking contractors with proven records to build something safe. (If you’re looking to stop bullets, go for a simple thick wall, not a thin metal layer.)

To own a Riot Shed is to acknowledge that paranoid fantasies of urban violence, distorted by a legion of grifters, not only live rent-free in your head, you’ve now paid at least $50,000 to house them in a shed in your backyard.

I very much enjoy writing like this, and reader support is what lets me take it from a weird, time-intensive hobby into part of my patched-together freelance income. Paid subscribers can comment on all my entries here, and I’ve included a survey in my paid posts so I can better respond to what it is that subscribers actually want me to cover.

This specific issue of my newsletter leans heavily on the research of anthropologist Martin Pfieffer, who is an invaluable scholar of everything weird about humans and the nuclear enterprise. If you liked my dive into the weird world of fallout shelters, I bet you’d love what Marty discovers and shares on his Patreon.

That’s all for this fortnight. Thank you all for reading, and if you’re in the mood for more newsletters, may I recommend checking out what we’re doing over at Discontents?